Parley AIR: Understanding Ocean Currents

A major ocean current system is slowing and could collapse in the next century. The fallout would be catastrophic.

Until early this year, the notion that ocean currents could stop was just a theory.

It was something scientists first suggested in the 1960s — that an influx of freshwater into the Atlantic Ocean could cause one of the most prominent ocean current systems on the planet to grind to a halt. Now it’s a real fear (and a meme). Two major studies in the last year have shown that faster-than-expected climate change and glacial melt have put the planet in position for a major collapse to happen, potentially soon.

When exactly we will hit an Atlantic tipping point remains unclear. Right now, scientists estimate it could happen sometime between next year and the end of this century. As the authors of the latest paper, published in Science Advances, explained, “this is bad news for the climate system and humanity.” We’ll get to ‘why’ below.

Oceanographers caution against oversimplifying complex current systems and say viral headlines are conflating the near-surface Gulf Stream with the entire deep-reaching Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC). They’re connected, but distinct. Fact-checking articles also emphasize the uncertainties behind the current slow-down. It’s confusing. No one can say for sure what will happen or when.

While the unknowns are many, scientists agree the oceans are not immune to human activity and urge a rapid reduction of carbon dioxide emissions. Since the Industrial Revolution, humans have pushed the oceans closer to the brink. We fill our vital ecosystem with upwards of 10 million metric tons of plastic every year, and industry is poised to mine the deep sea before we even understand this realm. Sea surface temperatures are still at record highs, and now the critical and delicate forces that keep ocean water moving between the equator and the poles could stop as a result of climate change.

In this AIR Guide, we honor a system no one wants to break — the one circulating ocean currents that affect global climate, weather and other conditions that make Earth habitable. Here, we look into the motion of the ocean and what to expect should AMOC collapse.

Take the Parley AIR Pledge and receive our newsletter

The Global Ocean Conveyor Belt

What are ocean currents?

The oceans have gigantic natural conveyor belts that circulate seawater around the globe.

Because Earth is a sphere, different parts of our planet absorb more solar rays than others, meaning the oceans in these parts hold more heat. Without ocean currents to redistribute this heat around the globe, surface temperatures would be extreme and there would be much less inhabitable space.

Ocean currents regulate Earth’s climate and help maintain the delicate balance of life here. Without them, other biodiverse carbon sinks, like rainforests, can’t survive. It’s all connected.

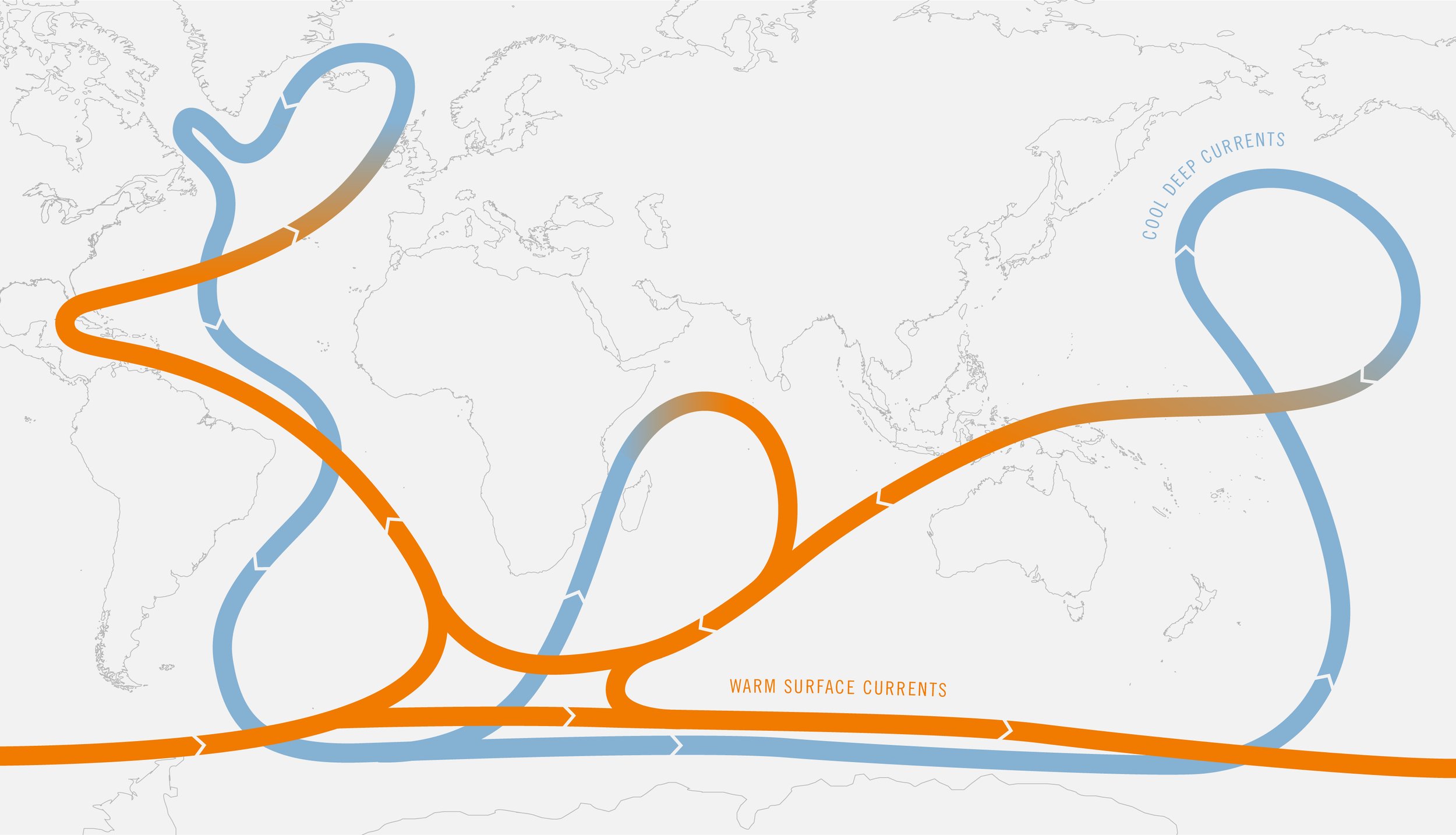

There are two types of ocean currents. Surface currents mobilize the top 10% of ocean water and form gyres, or pools of circulating water. Deep ocean currents move the 90% of water that lies below the surface. These two types of currents work together to keep gigantic pathways of water circulating around the planet.

Ocean currents are moved by wind, the tides and changes in water density. Features on the ocean floor cause these currents to speed up, slow down or change direction in certain places.

The Coriolis Effect

The rotation of the Earth plays a key role, too.

As Earth rotates, air in the Northern Hemisphere moves upwards from the equator, traveling slightly eastward towards the North Pole. At the same time, air from the North Pole travels to the equator, traveling slightly westward. The same thing, but in the opposite direction, happens in the Southern Hemisphere.

This phenomenon — called the Coriolis effect — forms water circuits, or gyres, in surface currents. Surface currents play a vital role in climate, distributing heat around the planet.

The currents take warmed water from around the equator and cycle it north and south, to the poles, where they exchange it for cool water. This doesn’t just heat and cool the oceans, it keeps all of Earth at the right temperature.

Deep ocean currents are mostly driven by changes in water density, meaning how closely water molecules are packed together, which can change based on temperature and how much salt the water is holding. Cold, salty water is more dense than warm water, so it sinks, pushing warm water towards the surface, a process called thermohaline circulation. This moves water around the entire planet in gigantic, reliable currents — called The Global Conveyor Belt — that weave between continents and the seven seas.

Climate change and ocean currents

Usually, it takes about 1,000 years for a single drop of water to make its way around the entire Global Conveyor Belt. But warming sea temperatures and an influx of freshwater from melting glaciers are disrupting the natural rising and sinking of cold and warm ocean water. This is slowing ocean currents — and scientists are trying to understand when they may stop all together.

Two recent studies have predicted that the Gulf Stream system — a strong surface current that carries warm water from the Gulf of Mexico through the Atlantic Ocean as far north as Northern Europe — isn’t just slowing down, but is at extreme risk of stopping altogether.

Scientists have a term for vital ocean currents slowing to a halt: Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, or AMOC for short. In 2021, it was already known that AMOC was at the slowest it had been in 1,600 years. But this was the first time scientists recognized warning signs of a tipping point, a point of no return when it would be impossible to stop human-created climate change from eventually causing currents in the Gulf Stream system to stop.

This would have catastrophic consequences for the planet and oceans.

If the AMOC collapses, it would irreversibly disrupt rains that people in India, South American and West Africa depend on for food. Europe would be hugely impacted. The continent would experience more storms, less rain and become colder, making it much more difficult to grow food. Sea levels would rise even more along the eastern coast of North America. A collapse would disrupt the climate keeping what is left of the Amazon rainforest stable. It would also limit the oceans’ ability to sequester and store carbon. Once the collapse starts, these changes would occur about 10 times faster than they do today, meaning adapting to the new normal would be virtually impossible.

One major source of AMOC slowing is the melting of Greenland's ice cap. This melting — which is being sped up significantly by climate change — adds 400 billion tons of freshwater to the oceans every year, impacting its salinity. At the same time, ice in the Arctic is melting at an unprecedented rate, causing even more freshwater to reach the oceans via Arctic rivers.

Scientists have now published studies in 2022, 2023 and 2024 warning that we could reach a tipping point that would cause the AMOC to collapse as early as next year, but it may not happen until around 2095.

The most recent study, published in February 2024, simulated changes in temperature and ocean salinity in the southern Atlantic Ocean, between Buenos Aires in Argentina and Cape Town, South Africa, over a span of 2,000 years. It found that a slow decline in AMOC could lead to a sudden collapse over about 70 years.

Until now, the notion that AMOC would collapse was considered to be a theory, and many guessed it wouldn’t be shown to be a real possibility once climate models predicting it were adjusted to include all climate inputs. But the new study showed the idea of AMOC collapse is not a theory at all and is the end result of the continuous slowing we’re seeing. If we don’t alter climate emissions at all, the 2023 study estimated AMOC collapse will start around mid-century.

Coping with climate anxiety

If you feel like this is unimaginably heavy, you are not alone. Google searches for ‘climate anxiety’ soared by 565% in 2021, and the commentary on social media is telling of collective overwhelm.

No one knows what level of CO2 would trigger an AMOC collapse. As Niklas Boers, one of the researchers behind the AMOC study told the Guardian, the odds of a collapse increase with every gram of CO2 released. “So the only thing to do is keep emissions as low as possible.”

We’ll add that it’s also important to shore up mental health for the long haul. Getting involved with education, community outreach and advocacy groups may not end climate change, but it can bolster wellness alongside solutions. A 2022 study by Yale researchers found that getting involved with climate action helps stave off depression associated with climate anxiety. Creating community around climate advocacy helps people feel less alone and makes climate anxiety less debilitating.

If you’re unsure where to start, listen. There’s a growing number of podcasts on the topic of climate anxiety. Here’s a few we recommend:

Climate Change and Happiness has created a space for people to talk about their climate anxiety and how they’ve found ways to cope.

How to Save a Planet is a great place to go if you’re in need of content that will motivate you to take climate action in manageable ways.

Outrage + Optimism acknowledges that we have a right to be anxious about the dire state of climate change. Dealing with climate grief is a great episode to start with.

One-on-one therapy can help, too. Certain countries, including the U.S., allow therapists to designate themselves as climate anxiety specialists. If you have access to mental health resources, you can try searching for climate-aware therapists in your area to find someone who understands how to work with people who have climate anxiety.

Finally, there’s our favorite subject: the oceans. Studies show that time spent on or near the water does good things for your brain. The sights, sounds and smells of the sea have been scientifically proven to reduce stress, lift spirits and inspire creativity. Ocean conservation is self-care. Pass it on.

TAKE ACTION

Read up, make noise, spread the word and give others the tools to do the same. Systemic change won’t come unless we demand it.

IG @parley.tv | FB @parleyforoceans

#ParleyAIR