Parley AIR Social Justice: Pollution Has No Boundaries

The oceans are an all-connecting link for the world’s plastic

“Everything is interconnectedness.”

Alexander von Humboldt

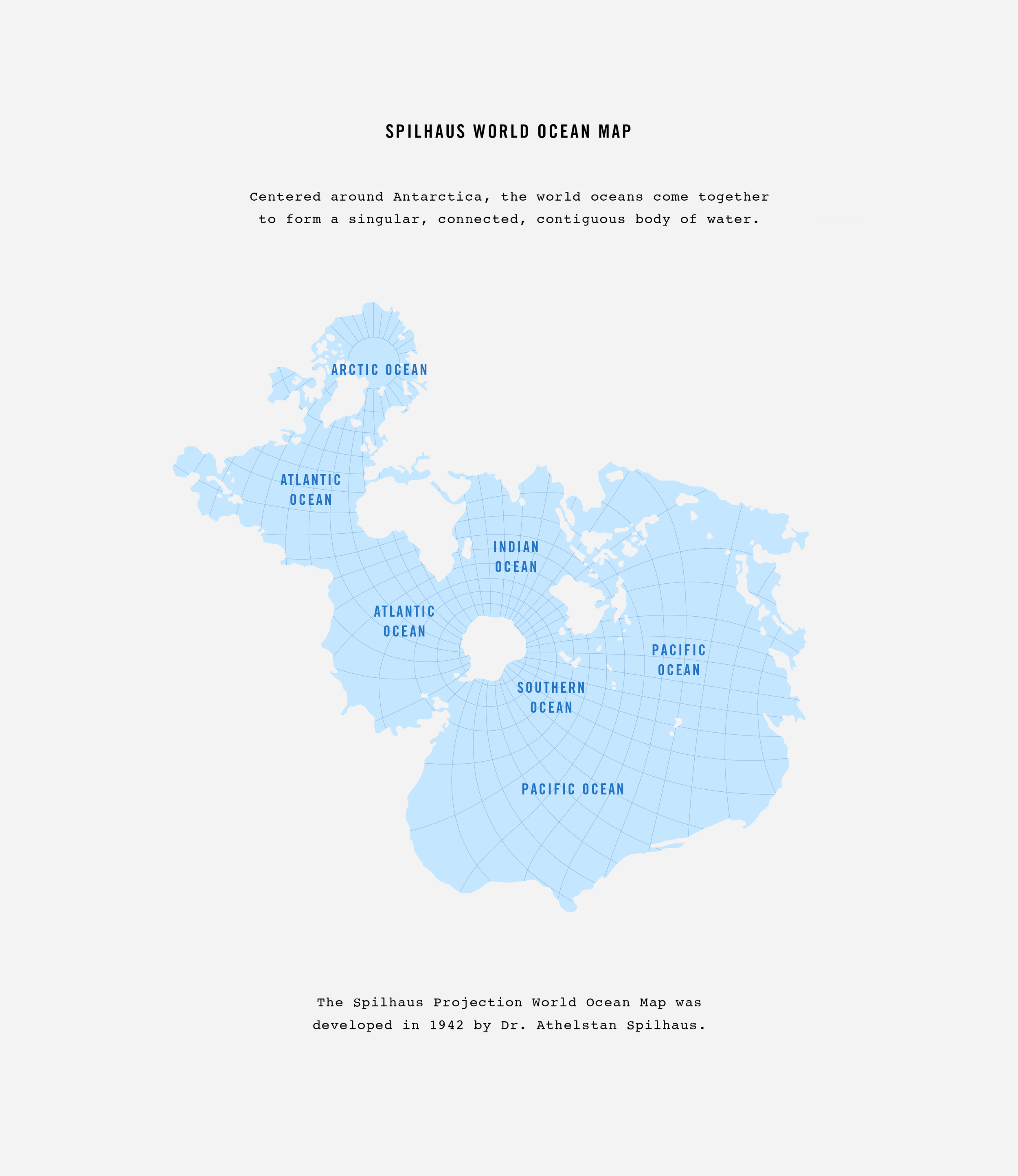

The oceans move across the planet like our blood moves through the veins in our bodies, connecting every organ, every person, on Earth. A single wave can travel thousands of miles before it makes landfall, transferring energy from a disturbance in the middle of the ocean to the shore. Water moves in a continuous loop through sea, sky and land. Our oceans connect us all.

This connectivity is the basis for life on Earth. It also means that any problem that impacts our oceans is never entirely local, it’s always global. And that includes our plastic litter problem — all 14 million tons of it that enter our oceans every year.

In part two of our three-part series on social justice and plastics, we’re focusing on the interconnectedness of the plastic pollution problem, and how ocean currents carry plastic far and wide, moving plastic trash far from the countries that produced it, to communities that are disproportionately forced to live amongst it.

Take the Parley AIR Pledge and receive our monthly AIR newsletter

The plastic pollution highway

Plastic makes up 80% of all marine debris — that includes every part of the oceans, from surface water to deep sea sediment. But that doesn’t mean this pollution only impacts creatures that call the oceans home. It gets everywhere.

Since plastic never breaks down — it only breaks up into smaller pieces — plastic never goes away. Instead, microplastic shards end up in virtually every corner of the planet, including in the deep tissues of our bodies, the water we drink, and even in human placentas. It also travels in the air we breathe — in 2020, French and Scottish researchers found microplastics hitching a ride around the globe on seabreeze. In 2022, researched from microplastics deep in human lungs.

Other times, plastic pollution maintains its original form, and travels thousands of miles around the oceans before washing up on distant coastlines (microplastics do this, too). This is because the ocean is dynamic, and ever-moving.

Oceans have currents, predictable paths that seawater travel along, circulating water and whatever debris happens to be in those waters. (Currents also create our weather and impact our climate and the temperature of our oceans in different places.) This movement also means that plastic trash has no boundaries. The plastic that enters the ocean in Japan, for example, often shows up on beaches in Alaska or Hawai'i. It also means that the world’s largest plastic polluters, usually wealthy nations, are often not the ones that ultimately deal with the consequences of their waste.

Even when plastic waste does land on their shores, it often washes up on remote beaches far from where the plastic pollution entered the oceans in the first place. Per capita, the U.S., U.K., South Korea and Germany are the world’s biggest plastic waste producers. When that plastic waste enters our oceans, it doesn’t stay on local coasts.

Thanks to winds and ocean currents, plastic travels thousands of miles before washing up on faraway beaches. For example, studies have shown that plastic waste that enters the Atlantic Coast hitches a ride on a massive current called the Thermohaline Circulation and travels as far north as the Arctic. In 2017, researchers traced plastic pollution along the Greenland coast directly to the coasts of northwest Europe, the U.K. and the East Coast of the U.S.

A study by researchers in Florida found that weak ocean currents create microplastic hotspots deep in the water column, where these bits of “missing plastic” — which we know should be in the oceans, we just haven’t known where — get into the food system from the bottom-up. Most of what they found were higher density polymers commonly used in paints and textiles like clothing, ropes and fishing nets.

Scientists believe that when microplastics are trapped deep in our oceans, zooplankton mistake them for food. The plastic inhibits these tiny marine animals’ ability to sequester carbon and slow climate change. And since plankton and zooplankton are at the bottom of the marine food chain, the microplastics these creatures consume make their way into bigger fish, and ultimately, our plates.

Borderless documents local communities dealing with contamination and a lack of waste handling.

Case study: Hawaiʻi

Ocean Uprise beach cleanup, Hawaiʻi.

Thanks to their position in the Pacific Ocean, the Hawaiian Islands have become a dumping ground for the world’s marine plastic pollution. The chain of islands sit at the intersection of the Pacific Ocean’s powerful currents — the same ones that pushed our marine trash into the Great Pacific garbage patch, which sits just east of Hawai'i. As a result, Hawai’ian beaches collect decades of plastic pollution from all over the world.

The Hawai'i Wildlife Fund estimates that 96% of the trash that washes ashore the state’s beaches every year — about 20 tons of it — is plastic. Nowhere is this more stark than Kamilo Beach, a remote, hard-to-access beach on the south-eastern tip of Hawai'i’s Big Island.

Kamilo beach has been called one of most plastic-polluted places on Earth, despite it being on an island that’s home to less than 200,000 humans. Beach clean-ups have recently collected parts of TVs, broom mops, toothbrushes and even a sunscreen bottle from the 1950s on Kamilo Beach. During the first clean-up, in 2003, volunteers removed 50 tons of marine debris from the beach in just three days.

In October 2018, Greenpeace located a massive tangle of fishing nets and rope 700 nautical miles northeast of Hawai'i, in the North Pacific Gyre. (Gyres act as the conveyor belts of the ocean, circulating massive amounts of water.) With the help of NOAA, the team had been tracking the ghost net’s migration across the Pacific Ocean. By April, trackers showed the 1,500-pound mass of garbage had made landfall on the Northeastern shores of Maui. So Parley’s Kahi Pacarro headed out to the remote stretch of coastline to help clean it up, making sure it wouldn’t continue to pollute the oceans or coastlines. To date, Parley beach clean ups have removed 60,000 pounds (about 27,000 kg) of plastic pollution from Hawai'ian beaches.

In recent years, Hawai'i has seen a drastic reduction in plastic pollution along its beaches, and although beach clean-ups are a crucial part of the solution, the reduction is largely due to cyclical ocean currents.

“What’s very interesting is the fact that the garbage patch has shifted more towards North America and resulted in a drastic reduction in plastic accumulation on our shores,” says Kahi. But the shift is temporary. “The plastic influx is only a few years away again. With the shift from La Nina to El Nino, our beaches are expected to get inundated with plastic once again within the next three years.”

Case study: Midway Atoll

About halfway between Hawai'i and the Asian continent sits the Midway Atoll, a nearly uninhabited (by humans) chain of islands has quietly been overtaken by our plastic trash.

Like Hawai'i, Midway Atoll sits in the center of the mighty Pacific Ocean currents. This means that, despite being 1,300 miles from the nearest shoreline and producing virtually no plastic waste of its own, Midway Atoll has become a devastating dumping ground. It’s also a marine sanctuary for the Albatross, iconic oceanic birds that live and nest on shorelines. These birds ingest plastic straws, cotton swabs, bottle caps and kids’ meal toys. The pollution kills many of them before they’ve had a chance to produce their young.

Nearly 70% of the world's Laysan Albatrosses and almost one-third of the world's Black-footed Albatrosses nest on the atoll every year. It’s a critical habitat. (Parley collaborator and artist Chris Jordan documents the beauty and fragility of the Albatross in his film, Albatross).

The Midway Atoll is just one example of wildly remote islands that are both critically important seabird habitat and plummeted by plastic pollution. The Coco Islands, an archipelago of 27 tiny islands about 1,300 miles off the coast of northwest Australia, are in the middle of the Indian Ocean. The islands are uninhabited by humans and rarely visited, but this hasn’t saved them from the scar of human’s plastic habit. An estimated 238 tons of trash has washed up on the shores of the islands, a quarter of which are disposable plastic items like flip-flops, toothbrushes, straws and bottle caps, a 2019 study found. About 60% of the plastic debris that’s washed ashore the Coco Islands is microplastics, tiny bits of plastic broken down by sun, waves and wind that is extra difficult to clean from natural habitats.

Trailer for Albatross by Chris Jordan.

Parley beach cleanup, Cape York.

Case study: Cape York Peninsula

The islands off of Cape York Peninsula in Australia are home to 17 Indigenous communities. Although the islands are largely pristine, ocean currents still carry trash by the tons from the Pacific Ocean to the shores of the wild islands.

The Great Barrier Reef, our planet’s largest coral reef system, starts off the coast of the northern tip of Cape York Peninsula. So does a protected area called The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. The area is a Marine Park Zone that's a crucial habitat for corals, sea birds and nesting endangered sea turtles.

During these expeditions, the Parley team worked with local Indegenous communities on Cape York to get a clearer picture of how specific currents and reef channels impact where plastic pollution goes. The crew also removed 1,397 lbs (634 kg) of plastic from some of the most remote areas of the park. Learn more about the project here.

Parley x Gulf of Alaska Keeper cleanup.

Case study: Alaska

As climate change grips planet Earth, we’ll see more natural disasters. That is a fact. And each one of these is an opportunity for more plastic pollution to enter our oceans. We’ve already seen how it could play out.

On March 11, 2011, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake in Japan triggered a tsunami. Those massive waves pulled an estimated 5 million tons of debris from shore into the Pacific Ocean. By the end of that year, the same debris began showing up on coastlines in the U.S. and Canada. Carried by winds and currents, highway markers, plastic stakes, soccer balls, bottles, shoes, tangled fishing nets and even refrigerators continue to wash up along remote, sparsely populated, and uninhabited shorelines.

In 2016, Parley teamed up with Gulf of Alaska Keeper to organize one of the most ambitious marine debris recovery and recycling initiatives ever attempted. Together, we traveled to hard-to-reach Alaskan coastlines in Prince William Sound. It took 40 days of clean-ups to remove 2.5 million pounds of trash from 1,500 miles of rugged coastline.

Sri Lankan officials respond to nurdle and chemical spill.

Case study: Sri Lanka

Plastic — and the raw materials used to produce it — are also shipped all over the world via international waters. When ships sink in those waters, the world’s plastic pollution becomes disproportionately one country’s problem.

That was the case last year, when the X-Press Pearl cargo ship carrying nurdles — the building blocks of plastic — sank off the western coast of Sri Lanka. Eighty-seven containers full of 1,680 tons of lentil-sized plastic pellets spilled into the Indian Ocean. The U.N. called it the country’s worst maritime disaster in history, and, a year later, communities from Indonesia and Malaysia to Somalia are still cleaning up the pollution. Sri Lanka was particularly devastated. Mostly burned plastic nurdles are still releasing chemicals into Sri Lankan beaches and contaminating the sealife fishermen rely on for food and income. Sri Lankans also rely heavily on tourism, and the country’s golden beaches were a huge draw before the spill.

This is just one example of how the plastic pollution that enters our oceans in international waters is carried by currents, waves and winds to land, regardless of where its intended endpoint was initially.

What you can do to break the cycle

🌎 Push our world leaders to drive structural change:

Individual actions add up and can’t be left out of the equation, but for the biggest shift to happen, the way humans think about plastic has to change. It’s not a distant threat to be dealt with in the future. We need systemic change from world leaders now that forces companies to stop producing single-use plastics made from fossil fuels.

The good news is, we’re already making strides. In March 2022, 175 nations met at the United Nations Environment Assembly in Nairobi. Their focus was to start a committee that would create a legally binding agreement that would end plastic pollution. The agreement isn’t slated to be announced until 2024. Until then: Get loud. Vote. Put pressure on those in power. Speak up. Repeat.

🙌 Support clean-ups around the world:

Your local plastic pollution doesn’t stay at home. Support the movement.

🐋 Take the Parley AIR Pledge:

If you haven’t already, join thousands of people like you who are committed to reducing their own plastic footprint and rethinking how companies create products. Learn more here.

TAKE ACTION

Read up, make noise, spread the word and give others the tools to do the same. Systemic change won’t come unless we demand it.

IG @parley.tv | FB @parleyforoceans

#ParleyAIR