Parley AIR: A guide to forever chemicals

The chemicals used to make plastic are contaminating everything, including us

You may or may not have heard of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), the so-called forever chemicals used to manufacture an incredible number of common products. The group of over 9,000 synthetic compounds are known to harm human health. They’re often called ‘forever chemicals’ because, like plastic, they never break down and stay in our bodies and the natural world indefinitely. And they are everywhere. They show up in coatings and paints, food packaging, cleaning supplies, shampoo, dental floss, nail polish, cookware, and firefighting foam.

Forever chemicals are a huge topic to dig into. They’re regulated differently in every country, which means that even if certain PFAS are banned in one country, they can still enter through imported goods. In the past couple of years, the toxic chemicals have grabbed the attention of lawmakers, who are in charge of setting standards on which forever chemicals, and how much, are allowed in our environment. But very little tracking was done until 2021, and still, there’s a lot we don’t understand about just how widespread PFAS contamination is. And since new forever chemicals are created all the time, and each is a unique compound, regulation is a moving target.

In this AIR Guide, we’re getting into why forever chemicals are so ubiquitous in modern day life, what we know about how they harm human health, how PFAS are getting into our bodies and what legislation is in the works to protect against them.

Take the Parley AIR Pledge and receive our newsletter

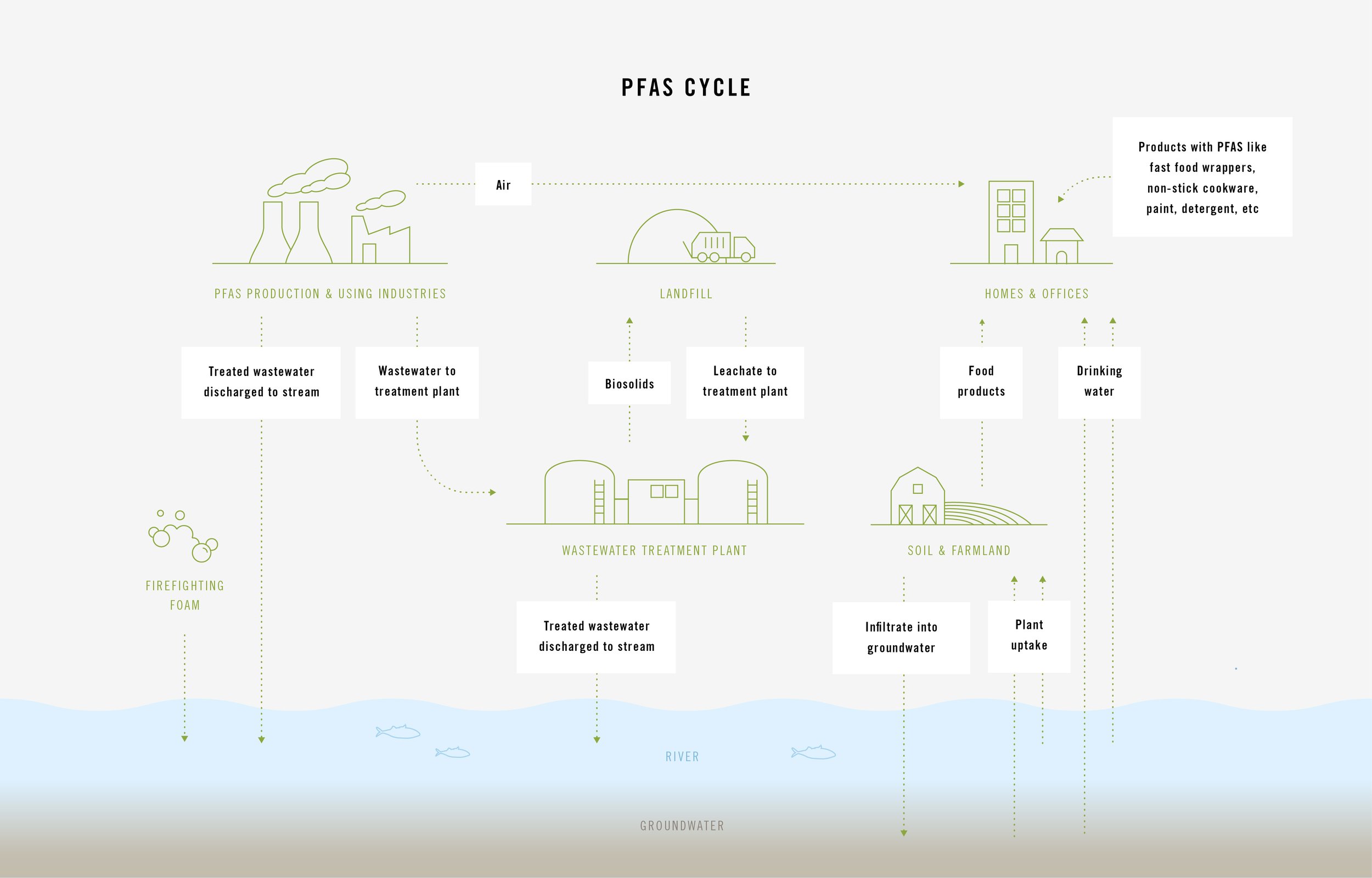

Reference: New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection

What are Forever Chemicals?

PFAS were first created in the 1930s, and have become omnipresent since then. They’re extremely versatile and used in a mind-boggling number of products, everything from the stain-resistant textiles, to medical devices, toilet paper, cookware and even makeup. They’re also used in plastic containers that leach the chemicals into food – even those sold to the public as “all natural” foods and drinks aren’t immune. Not only are there thousands of unique compounds to keep up with, PFAS and their replacements can be difficult to study since the chemicals are often proprietary information – meaning companies legally have a right to keep them secret. This means we don’t even know how to test for some forever chemicals.

In short: We don’t actually know how many PFAS, and how much of each one, are in the world around us. But we do know that PFAS accumulate and once they’re in the environment, they’re extremely difficult to clean up.

Governmental agencies like the EPA have known for years that PFAS are harmful, but waited to implement legislation. That delay allowed PFAS to accumulate in the environment – and in us.

Some of the most common and most studied PFAS are Perfluorooctane Sulfonate (PFOS) and Perfluorooctanoic Acid (PFOA), also called C8. They were once widely used in North America in everything from nonstick cookware to fabrics and stain-resistant carpet.

Over the past two decades, they’ve largely been phased out in the U.S. and Canada — but linger in the environment, and are still used elsewhere, which means imported goods that end up in these countries still often contain PFAS. In the U.S., PFAS continue to be used in special firefighting foam. The Pentagon in the U.S. plans to phase this exemption out by 2024 due to mounting clean-up costs associated with PFAS contamination.

The alternatives companies created to replace PFOA and PFOS have been documented to have similar health effects, including affecting the immune system, liver, kidneys, cancer, early deliveries during pregnancy and the delayed development of genitals.

Plastic collected during a Parley cleanup in Australia

PFAS AND PLASTIC

In 2021, an EPA investigation revealed that PFAS were probably a lot more common in single-use plastics than previously thought. Today, the most common source of PFAS in plastic is in containers that hold food and drinks, which allow the chemicals to seep into our bodies through our food. Microwave popcorn bags, pizza boxes, candy and fast food wrappers, are all known to contain forever chemicals.

Fluorinated plastic containers, made through a process that alters plastic containers so they can hold chemicals that would otherwise react with plastic, especially those used in food, probably represent a major new source of PFAS exposure. Fluorinated containers also hold personal care products like shampoo and makeup.

A 2011 study also suggests that large amounts of forever chemicals can leach from plastic and into the products they hold. The researchers measured PFAS levels in water that was left in a fluorinated container for a year. They reached 188,000 parts per trillion (ppt). That’s a huge amount. Some states allow as little as 5ppt in drinking water and public health advocates warn anything above 1ppt is dangerous for human health.

Earlier this year, people brought a class-action lawsuit against Coca-Cola for claiming their Simply Orange orange juice is “all natural” despite having been found to contain PFAS leached from the plastic bottle it comes in. It wasn’t the first time in recent years people have taken action against the companies using PFAS-containing plastic food containers.

In December 2022, citizens brought a similar lawsuit against a plastic packaging manufacturer called Inhance, which produces tens of millions of plastic food containers that contain PFAS.

Inhance treats plastic containers with fluorinated gas to create a barrier that helps keep products from degrading. The consumer groups say the process creates PFAS as a byproduct, including PFOA, one of the most dangerous of the class. EPA rules implemented in 2020 require companies manufacturing long-chain PFAS to submit for a safety review and approval. The people who brought the lawsuit say that Inhance failed to do so, and wanted a judge to require Inhance to follow this EPA regulation.

The groups also charge that regulators have known of the potential health threat since early 2021 but have failed to eliminate it.

Legislation only works if it’s enforced, and though it shouldn’t be left to people to ensure companies are following the laws meant to protect us from PFAS, the power of individuals taking action is huge – and one of the only defenses we have until PFAS stop being produced worldwide.

In fact, following a class-action lawsuit regarding the threats the chemicals pose to human health, as of 2005, the U.S. no longer manufactures PFOAs nor PFOSs – though they are still manufactured internationally and used in exported goods.

PFAS IN OUR OCEANS

PFAS are also found in the oceans and throughout the marine food web. A recent report found the chemicals in more than 330 species of wildlife.

Another study, by the European Food Safety Authority, found that fish and seafood were a key source of chronic exposure to both PFOA and PFOS. The chemicals travel easily, which means contaminated rivers bring PFAS into the oceans and ultimately, into the sea life we eat. The U.S. Food and Drug administration has been tracking PFAS in food since 2019. Since then, PFAS have been detected in canned tuna, fish sticks, as well as tilapia, cod, and shrimp.

A 2017 study in the U.S. showed that Americans who ate more fish and shellfish had greater PFAS concentrations in their blood than those who did not. More recently, a study published earlier this year found that people ingest the same amount of PFAS if they eat one U.S. freshwater fish as they would in a month’s worth of drinking water.

PFAS are lurking in other foods, too, but it’s impossible to know exactly which ones. There are big issues with tracking PFAS, which means we have just a small slice of the real picture. In the latest FDA tracking of PFAS in foods, the agency only looked for 20 of the some 9,000 known PFAS, and only looked in 92 food samples.

ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE

In March, the White House announced the first-ever national standard to address PFAS in drinking water. Right now, standards are mostly left to individual states to set, if they want to. One of the key aims of the move was to address the environmental justice issues wrapped up in the PFAS industry. Like mining, fracking and plastic manufacturing, PFAS pollution disproportionately affects low-income and BIPOC communities.

“Found in air, drinking water, and our food supply, PFAS pollution disproportionately affects disadvantaged communities and poses a serious threat across rural, suburban, and urban areas,” the administration wrote in a release.

One 2019 report found that nearly 40,000 low-income households and 295,000 more BIPOC households than expected lived within five miles of a site contaminated with PFAS, many of them military sites. PFAS contamination in freshwater lakes and rivers disproportionately impacts people who rely on fishing in these waters as a staple source of food. Some groups of refugees living in the U.S. fish as a cultural practice, but also as a means to secure an affordable source of protein.

In early 2022, the New York State Health Department published a study on Burmese refugees living in the Syracuse area of Upstate New York. They found that the population of Karen refugees living in New York State had elevated PFAS levels in their blood compared to the general population, and the source was likely sustenance fishing.

The future of forever

The E.U. and the U.S. both recently proposed legislation to ban or monitor PFAS. Most countries have either just started monitoring PFAS or don’t track them at all. The European Chemicals Agency states on its website that, “PFASs have been frequently observed to contaminate groundwater, surface water and soil. Cleaning up polluted sites is technically difficult and costly. If releases continue, they will continue to accumulate in the environment, drinking water and food.” Other countries, including Canada, have vowed to monitor, but not ban, PFAS.

Although the U.S. is one of the leading countries for PFAS regulation, it’s still not doing very much to keep PFAS out of the environment, and us. A loophole is allowing at least 600 known PFAS to remain in products produced in the U.S., despite known health risks. Again, action to close this loophole is being brought by individuals, specifically the non-profit EarthJustice, rather than the government or corporations. What regulations are protecting people from PFAS also largely depend on which state a person lives in.

Last April, the U.S. state of Maine announced a ban on sewage sludge spreading after extremely high amounts of PFAS were discovered in water, crops, cattle and soil on farms where sludge had been spread. The PFAS came from human and industrial waste collected from water treatment plants. Most of it is given away to farmers as fertilizers because it’s high in the nutrients plants need. It also reduces the need for petrochemical fertilizers. But currently, Maine and another state, Michigan, are the only ones monitoring PFAS in sludge. Maine’s ban also doesn’t take effect until 2030 and since PFAS accumulate in the environment and never go away, that still leaves years for more PFAS to enter the food systems through farms.

Parley beach cleanup in Brazil

WHAT CAN WE DO?

Big change happens at the top, but it usually starts at the bottom, with everyday people who push for solutions and don’t take no for an answer (shout out to Sharon Lavigne). We need to keep making noise and educating ourselves and those around us on the dangers of PFAS to keep moving forward and putting pressure on those who have the power to make sweeping shifts and widespread changes.

Consider starting your own petition – like the people who went up against pollution giants like Coca-Cola and Inhance. Here’s a petition you can sign to get started. Its aim is to push the EPA to ban all non-essential PFAS in the U.S. Use the petition to educate the people around you about how incredibly widespread PFAS are across the world, and why companies need to stop creating products that use the chemicals.

Ultimately, forever chemicals have to be phased out and replaced with non-toxic materials that don’t harm us or our planet. Put pressures on the companies that are some of the worst PFAS offenders: duPont, 3M Co., Chemguard Inc., Kidde-Fenwal Inc., National Foam Inc. and Dynax Corp. Tell them, and the people around you, that these companies need to not only stem the stream of new forever chemicals being created, but clean up the PFAS that have already accumulated in our environment.

Luckily, scientists are working on figuring out how to do that, but it isn’t going to be easy, and by no means is it a long-term solution.

Cleaning up existing PFAS is crucial, and having the technology to do so isn’t a replacement for banning the chemicals from being used in the first place. Green chemistry is a budding scientific focus that’s exploring solutions to PFAS contamination, but this will take time, money and infrastructure.

Change can happen, and will happen. We can end the Toxic Age and create a future of true collaboration with nature.

Parley is part of the call for a Material Revolution – a complete upheaval of the plastic- and chemical-ridden status quo. Back in 2017, Parley Founder Cyrill Gutsch sat down with Suzanne Lee, Founder of Biofabricate, another organization pushing for manufacturers to stop producing harmful materials and replace them with viable alternatives that will safeguard humans, animals, plants and the planet we share.

Listen to the talk here to learn more about the Material Revolution and how you can push brands to be a part of it.

Ways to reduce your exposure to PFAS at home:

Filter your drinking water. The NSF has a list of recommended filters here

Switch nonstick cookware for cast-iron, stainless steel or glass.

Replace plastic food storage containers with metal or glass alternatives.

Cook more using fresh ingredients; take-out containers can leach into hot foods.

Avoid stain-resistant carpets and upholstery, and don’t use waterproofing sprays.

Look for the ingredient polytetrafluoroethylene, or PTFE, or other “fluoro” ingredients on product labels, including cosmetics.

Don’t eat (or limit) microwave popcorn or greasy foods wrapped in paper.

Swap out your dental floss for a natural wax or uncoated alternative.

Source: PFAS-REACH (Research, Education, and Action for Community Health) project, funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences

TAKE ACTION

Read up, make noise, spread the word and give others the tools to do the same. Systemic change won’t come unless we demand it.

IG @parley.tv | FB @parleyforoceans

#ParleyAIR