Dawn Wright: Rolling in the Deep

We speak to the history-making scientist about interconnectivity, the darkness of Challenger Deep, and the light she sees in the world

Dawn Wright and Victor Vescovo celebrate a successful expedition

Dawn Wright knew when she was just eight years old that she wanted to study the ocean for her whole life. Inspired by watching The Undersea World Of Jacques Cousteau every Sunday in her living room, she became enchanted by the world just outside her door and the magic of the volcanic island that she lived on. This led to a life in the library poring over books about oceanography and science, consuming everything that she could about the different schools that trained professional oceanographers. It worked – Dawn graduated from Texas A&M University with a masters degree in oceanography and in 1994 received a PhD from the University of California, with a dissertation titled: From Pattern To Process on the Deep Ocean Floor: A Geographic Information System Approach.

Dawn is 62 now and is the chief scientist at the Environmental Systems Research Unit (Esri), a world-leading geographic information system and spatial data science software company. Its technology is used by governments and conservation organizations, while it’s also in over 10,000 universities. Her work at Esri focuses on facilitating the connection between Esri and the scientific community, especially facilitating scientists doing their research with geospatial technology.

Last year, on July 12, Dawn descended to Challenger Deep, the deepest point on our planet, reaching areas of the seabed that had never been explored before. Alongside retired naval officer and undersea explorer Victor Vescovo, the pair reached a depth of 10,919 meters in a submersible, where Dawn used high-resolution sonar to map a part of Earth that has never been seen before in so much detail. Normally, we think of explorers in a different light – up in space, or venturing across land many moons ago. But Dawn is an example of a different type, questing for the answers that we still need about our planet in the present day, particularly in its largest ecosystem: our oceans. We spoke to Dawn about making history on the Challenger Deep expedition, what it’s like down there, and the darkness and light of life on Earth.

"We saw tiny creatures that do live down there such as the anemones and the sea cucumbers, the little arthropods, these little creatures that can withstand the 16,000 pounds per square inch of pressure, living in complete darkness. Those small, seemingly insignificant creatures, along with insignificant me and my colleague Victor making it all possible, are part of our little community. We are part of it too, we are part of the totality of life on this planet and, pivoting to broader thoughts about life on the planet and the miracle that is life on this planet, we all matter and we're all interconnected."

Dawn Wright, Esri Chief Scientist

Q & A

You studied geology and then you got a Masters in oceanography. How and when did your passion for the ocean start? Where did you grow up?

I grew up in the Hawaiʻian islands. So that will do it! My family is from the East Coast of the US but my mother actually played a larger role in guiding where our family ended up through her career in teaching. My father was a high school basketball coach and a failed NBA recruit. So my mother took the lead and she got a teaching position in Hawaiʻi and so we moved there when I was six. I was raised in Hawaiʻi and spent a lot of time at the beach, doing a lot of swimming, body surfing and exploring. That is part of the culture of Hawaiʻi too, to enjoy but also to hold the ocean as sacred, as life giving. It's a natural part of everyday life there.

From the age of eight, I decided that I wanted to study the ocean as a career and I was encouraged at first by watching Jacques Cousteau on TV. I grew up in the 60s, and it was a wonderful time because the entire country had pretty much only three choices of television programming. There wasn't this overabundance of streaming channels and cable TV and there was no social media. Everyone watched these three networks and on one network there was always the undersea world of Jacques Cousteau on Sunday nights followed by the wonderful world of Disney. That was my steady diet of science communication! Just about everyone who watched Jacques Cousteau was enthralled by it, but I found out later on that he was more of an activist, more of an underwater photographer than a scientist.

I really wanted to be a scientist and I figured out that I lived on a volcanic island, then I found out about the origin of the island that I grew up on, Maui. I had a chance to visit the Haleakalā volcano and I thought ‘well if there are volcanoes on the ocean floor, I surely want to specialize in that?’. So it becomes ‘how do you do these sorts of things?’ It's like for young people who want to become astronauts, how do you get into that? How do you become that or people who are enthralled by anything really, by filmmaking or animation, how do you do it? I learned by reading books in an actual library, by sitting down on a table with actual books and reading about oceanography, science and reading about the various schools that trained professional oceanographers.

That led me to geology as an undergraduate major. I came away with an undergraduate degree in geology and went into a graduate programme in oceanography with a specialty in geological oceanography. Then I went to sea for three years with what is now known as the International Ocean Discovery Programme, but at the time that I joined it it was the Ocean Drilling Programme. I was at sea for three years as an ocean-going technician and learning much much more.

It was a series of two month sailing expeditions through the Indian and Pacific, right? What did you learn about our oceans over that three year period?

There is nothing like going to sea on an actual research vessel with scientific objectives to open up all kinds of worlds. My first expedition as a marine technician was actually to Antarctica. I was sent to the Weddell Sea and it was just mind blowing because you see the penguins, the seals and the albatrosses. I went to my first penguin rookery in Punta Arenas, Chile but as a technician you are responsible at sea for helping the scientific party to get their work done. Drilling vessels are out for two months because you spend so much time anchored to the sea floor bringing up cores of sediment and rocks. Then the technical crew is responsible for processing those cores, getting them split in half ready for the scientific party to examine. We also were responsible for running the initial scientific tests on the cores, running them through magnetometers and doing chemical analyses of the sediment samples. My main job was to process scientific reports – I had to read and edit all of the reports that came from the scientific party as they did all of these experiments on these cores and interpreted what the cores were saying about the history of the earth in that particular location. There was no better training for me, I'm ever thankful for it.

You've spent about 40 years working in our oceans every day – what change have you seen in the oceans over that period?

Boy, when you put it that way….40 years! I hadn't even counted.

I didn't mean to scare you!

Well one of the big changes is that the oceans are heating up. They're warming, the temperatures are getting alarmingly high because of all of the heat. The oceans or the ocean as a unified global system of our planet is absorbing around 90% of the excess heat that we're generating from our activities on land. So that is one of the biggest changes and you can see that in our weather patterns from day to day, along with our long term climate view. We're talking about this in California right now because we are in the grip of yet another series of atmospheric rivers fuelled by the warmer ocean. So we're going to get these storms that are more powerful, that carry more water and more precipitation. For us in California, living on land, we are experiencing this as a coastal state but everywhere that you are on the planet, you are affected by this warming of the ocean. The other big consequence that we see is the growing acidification of the ocean because as much as 25% of the greenhouse gasses that are emitted on land are being absorbed. That's making the ocean more acidic, the coral reefs are in danger and then there’s the lack of oxygen. The ocean is losing its oxygen, especially in the deeper portions as well. Those are the big three – the temperature, the acidification and the oxygen.

Dawn practices getting in and out of the sub

This map was used to navigate and track the sub’s position during the survey of Challenger Deep / cartography by Rochelle Wigley

You just mentioned the deepest points of the ocean – this area of the world has been a big part of your story over the past year with your expedition to Challenger Deep. How did you feel when you kind of found out you were going and you were going to be the first Black person to travel there?

The big thing for me was getting the opportunity to go as an oceanographer first. I’m someone who has studied the ocean for so many years and been to all of the major ocean basins in terms of my research work but there are some areas that are holy grails for many of us. I had studied the Tonga trench and I was involved in mapping that trench and having done that – of course you want to go to the deepest trench to visit it but if you're not able to get the funding or if you're not involved in a specific scientific study that is studying that, then your chances are slim to none of actually getting to go. I was overjoyed at just getting the opportunity to go as an explorer.

Being the first Black person is the icing on the cake, although I would like to hope at some point that we don't have to make these types of pronouncements in terms of the first man, the first woman, the first Black person, the first Asian person.

Also on our expedition was my good friend Nicole Yamase who went the year prior as the first Pacific Islander. She's from the federated states of Micronesia. These are things that matter now, but I look forward to our society evolving to the point where we are all looking at each other with equality and respect and we don't have to make these pronouncements.

But until then, yes that was very precious to me and very significant, also because of the way that it is being viewed by the Black community globally. Upon returning I got a nice tag on Facebook from Derek Davis who works with the National Association of Black Scuba Divers. He gave a presentation to elementary school children recently and showed them the CBS news snippet of me and Victor Vescovo following our dive. All of the questions, all of the inspiration coming from those children, it's just amazing. Kids need to see this, they need to dream. It certainly was the case for me.

What’s it like down there?

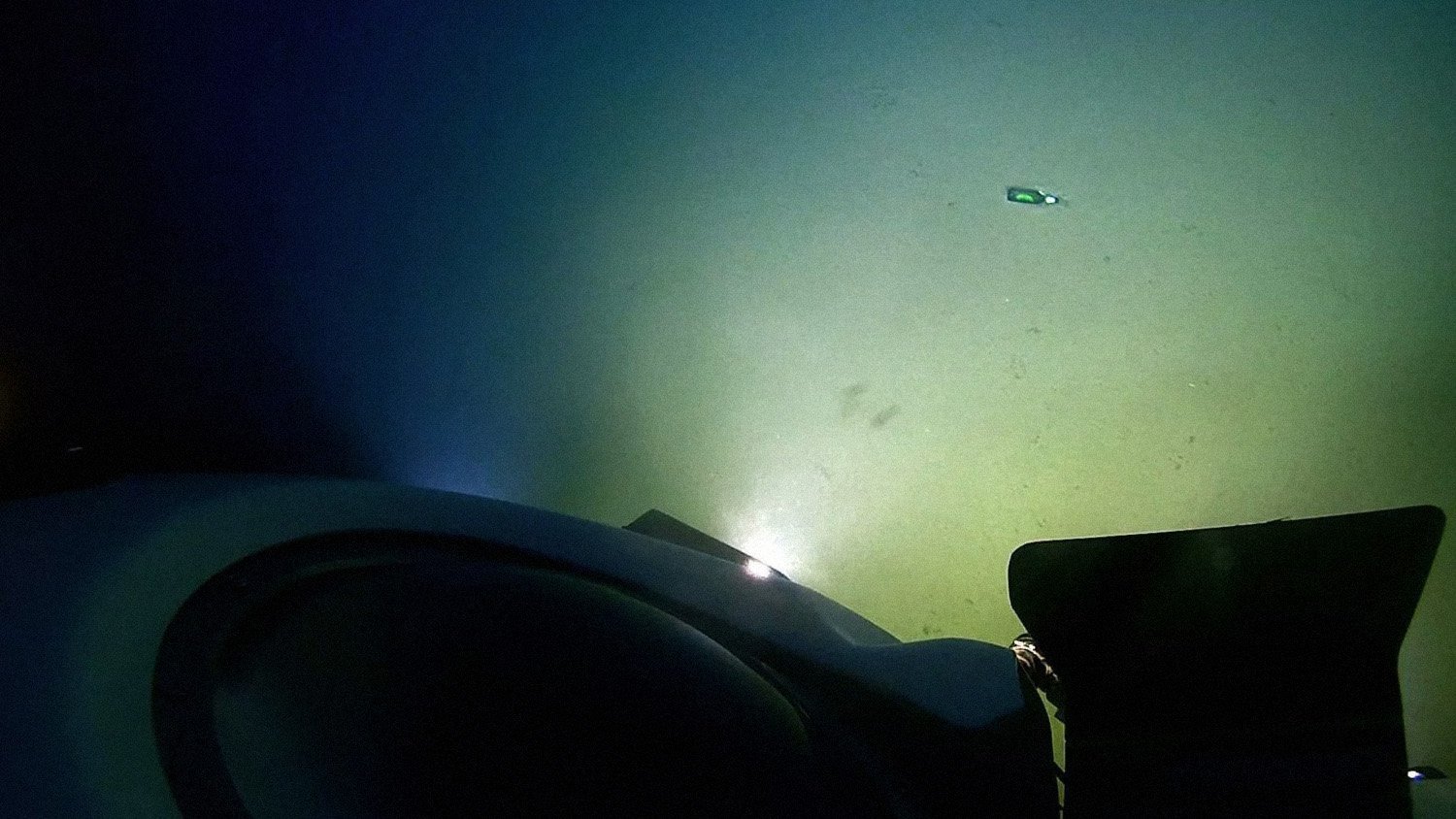

It's very quiet, there are no large creatures, the pressure is too great for even just a regular-sized fish to survive in the deepest part of Challenger Deep. Scientists who study the creatures that live in the deepest parts of the ocean surmise now that 8 or 9,000 meters is about the deepest that fish are known to exist. It's exhilarating, and it never gets old, the fact that you're descending through the lit zone of the ocean, which is beautiful aqua blue, then things slowly turn to gray and then pitch black. You hope that you're also treated to a firework show by the bioluminescent creatures that live in that zone of the ocean. What is not known by most people is that the twilight zone, that zone just as the ocean turns dark, that is where most of the biomass in the ocean is. We were treated to a nice little firework show by bioluminescent jellyfish and siphonophores.

In fact, Victor stopped our descent at around 9,018 meters and started flashing the lights of the submersible to attract these creatures and they flashed in return. We had a little bit of communication with them and then we continued our descent. So that is always a thrill.

Then when you actually get to the bottom….that is amazing and it was really emotional for me. There was really nothing to see at the place that we landed. It was fairly level and covered with sediment. Victor and I were both shocked because we landed on the sedimented, fairly flat portion within this depression in Challenger Deep. We were in the Western Pool. There's an Eastern, Central and Western pool.

Two white, tube-dwelling anemones of the genus Galatheanthemum grow out of a basaltic rock formation, found in Challenger Deep

How do you prepare for that journey? Is there training for adjusting to pressure, anything like that?

No, it's not like astronaut training at all. You don't have to worry about being subjected to G-forces and motion sickness, all of the training that astronauts go through. In my case I was a mission specialist because I was operating the computer programme that was gathering data from a prototype-mapping instrument that we put on the bottom of the submersible. Our main objective was to see if that instrument in its engineered configuration could be the first to survive the crushing depths at full ocean depth. We didn't feel any changes in pressure. Everything is taken care of by the titanium sphere that we sit in. I did physical training just to get myself in shape for being at sea again. I had not been at sea for many many years and there's a certain amount of upper body strength and cardiovascular fitness that you need because you're constantly going up and down ladders and steps on a ship. Most of your movement is vertical. You don't really have a lot of horizontal distance to cover on a ship. You basically go up and down to get to the different decks of the ship. So I needed to get myself into shape for that and also to increase my flexibility from being in the submersible.

And you found a beer bottle down there, right?

Yes, we started our traverse so that we could start our observations and ready the mapping instrument to gather data but as soon as we started that, we happened upon a beer bottle on the bottom. We were shocked and disappointed, angry that this is what humans are doing to the planet and the effects even reach the deepest parts of the ocean. So one big lesson is do not litter, please! As they said when I was a little girl, ‘give a hoot, don't pollute!’ There was tons of speculation on social media as to the brand of the beer, but in my view the brand doesn't really matter. I know it's fun to know, but what's more important is that someone threw that bottle overboard illegally and polluted the ocean and this is just a small example of what's happening in catastrophic ways in the ocean to the point where we have this problem now of microplastics being entrained in the tissues of organisms, organisms that we end up eating. In fact, professor Alan Jamieson, one of the world's leading hadal biologists, made the discovery of eurythenes plasticus in Challenger Deep. This is a new species of amphipod, a small little shrimp-like creature that has microplastics already entrained in its tissues. So the genus is eurythenes but the species is plasticus and that is tremendously tragic.

We talked about astronauts a little before. They often talk about how their perspective on life and the Earth changes when they go into space. Do you get that same kind of feeling when you go to the deepest point of the earth?

I think it's a little different, speaking from my own experience. For me, I get the sense that I am both insignificant and significant. It's different because I am just at one small point on the planet's surface as opposed to being up in space with this broad synoptic view. For the astronauts on the moon, they saw the entire orb of the earth and for astronauts in orbit, they see vast expanses of the planet.

It's different being in a small submersible at one point in a very deep, dark place but at the same time seeing the evidence of tectonic activity there. We saw vast fields of boulders in the collision zone of the trench. We saw tiny creatures that do live down there such as the anemones and the sea cucumbers, the little arthropods, these little creatures that can withstand the 16,000 pounds per square inch of pressure, living in complete darkness. Those small, seemingly insignificant creatures, along with insignificant me and my colleague Victor making it all possible, are part of our little community. We are part of it too, we are part of the totality of life on this planet and, pivoting to broader thoughts about life on the planet and the miracle that is life on this planet, we all matter and we're all interconnected.

It struck me while being down in Challenger Deep how the oceans are heating up. The heat is circulated through these deepest trenches, all the way up to the surface of the ocean. Hence all of it matters and all of it is buying us time in terms of climate change. The negative impacts of climate change would be hitting us so much more terribly, so much faster, if it weren't for the ocean absorbing a lot of it. It’s keeping things at bay for as long as it can until we reach this terrible tipping point where even the ocean will not be able to help us. That's what struck me is, sort of like Dr. Seuss’s Horton Hears a Who!, that story where he discovers his whole world on a speck of dust or a little flower and they have their whole lives, their whole ecosystem there and they matter too.

The final thought for me on this is that all of us matter, all of it matters and everything that we can do to reverse the effects of climate change and also to reverse the hatred and the destructiveness of our lives and our societies, anything that we can do to stop that is all the most important work that we can be doing right now.

The entire Challenger Deep expedition crew

Crew members (L-R) — Nicole Yamase: the first Pacific islander to Challenger Deep, Kate Wawatai: submarine technician, Dawn Wright, Tamara Greenstone Alefaio: program manager of the Micronesia Conservation Trust

Earlier, we talked about the fact that it would be good to get to a point where we're not talking about the first Black person, the first woman, the first Asian person to do something. I agree with that, but I know that you’ve done some work in helping to diversify science, and there’s still work to be done. A lot of our world is seen through a white perspective. I wanted to talk to you about that and how you think that can be changed.

There are so many fantastic organizations that are working towards that now. In fact, I have the wonderful problem of not knowing exactly where to begin because there’s been so much work. Just before coming to speak with you, I was watching a documentary about Ruth Bader Ginsburg. She took up the mantle of gender equality throughout society and that is certainly a huge issue in the sciences and in the conservation community writ large. The fact that women, young women are still being harassed and abused out in the field as they are trying to do their science, that was a problem that I thought would be solved by the time I got to this point in my career. As a little girl in the 1960s, watching all of the civil rights unrest on TV, I thought ‘well by the time I become an adult, they will get this civil rights thing straightened out and our generation won't have to worry about a thing’, says the person now in her 60s who is involved with Black Lives Matter. The murder of George Floyd was certainly a trigger for so many universities, so many organisations, and so many companies that started racial equity initiatives. Some of it is sincere, some of it is not, but what I try to work on is to increase the sincerity and the action of these initiatives.

My colleague Clinton Johnson has really been a leader in terms of leading awareness and action in terms of diversity, equity and inclusion within my company Esri. Also my company produces software and services that can be used by communities to solve any number of problems, such as climate adaptation and mitigation, but certainly rolling back injustice in society, even just the basic area of environmental racism when it comes to where communities are located.

Where they're located matters, they're located near harmful polluting areas unjustly and our software can bring that to life, it can create the maps that show clearly where and I keep enunciating where because our motto at Esri is to optimise the science of where. That alone is very very powerful.

There are two organizations that I think are just fantastic. Black in Marine Science started as a hashtag on Twitter and there was such an awakening and opening up of people telling their stories through that social media campaign. Dr. Tiara Moore and her colleagues wrote that into their own non profit organization so they're doing tons of advocacy, education work, encouraging scientists, funding small projects. It has been a help to me to see all of these others as I thought that I was the only one for so long in terms of marine geology. There are so many of these wonderful young scientists all over the world who are Black, from all stripes, areas of life doing fantastic marine science.

Another organization is Black Women in Evolution Ecology and Marine Science. Dr. Asha de Vos is doing amazing work calling out deep sea mining issues. Dr. Ayana Elizabeth Johnson is on many many planes doing fantastic work on the climate and ocean policy front. Tara Roberts is a National Geographic explorer and part of diving with a purpose where Black scuba divers are diving on wrecks of slave ships to learn about and recover that history and to reckon with that too. There are so many. If we're looking at things through the lens or the perspective of just one kind of person or one gender, we're missing out on so much.

We've touched on human-caused climate change and greenhouse gasses. As we face this, what gives you hope?

It's the young people who give me hope and it's communities fighting back, companies and governments changing. I get a lot of hope through the newsletter of my friend and colleague Dr. Katharine Hayhoe who is one of the world's leading science communicators but also a fantastic, wickedly smart atmospheric and climate scientist. She is the chief scientist of The Nature Conservancy which is a close partner of ours at Esri. It's just wonderful to be her colleague. She has a newsletter now and her newsletter is full of good news, even in places where you think there is little to no hope. She lives in Texas and she keeps reminding us that Texas, despite its history, a place known as “the oil patch”, it’s the place where alternative energy is taking hold the most. The most production of alternative energy from wind is taking place in West Texas. She keeps reminding us.

So there are all of these reasons for hope, points of lights, points of inspiration that are going on everywhere and we certainly would love the media to focus on this a bit more too because we always hear about the corruption, the destruction, the bad things that are happening – and there certainly are bad things that are happening. But there's a whole lot of light in this world too.

Challenger Deep expedition images courtesy of Esri