The octopus’s garden flourishing at the bottom of the ocean

We speak to Dr. Beth Orcutt and Dr. Jorge Cortés about their stunning discoveries made aboard Schmidt Ocean Institute’s research vessel, R/V Falkor (too)

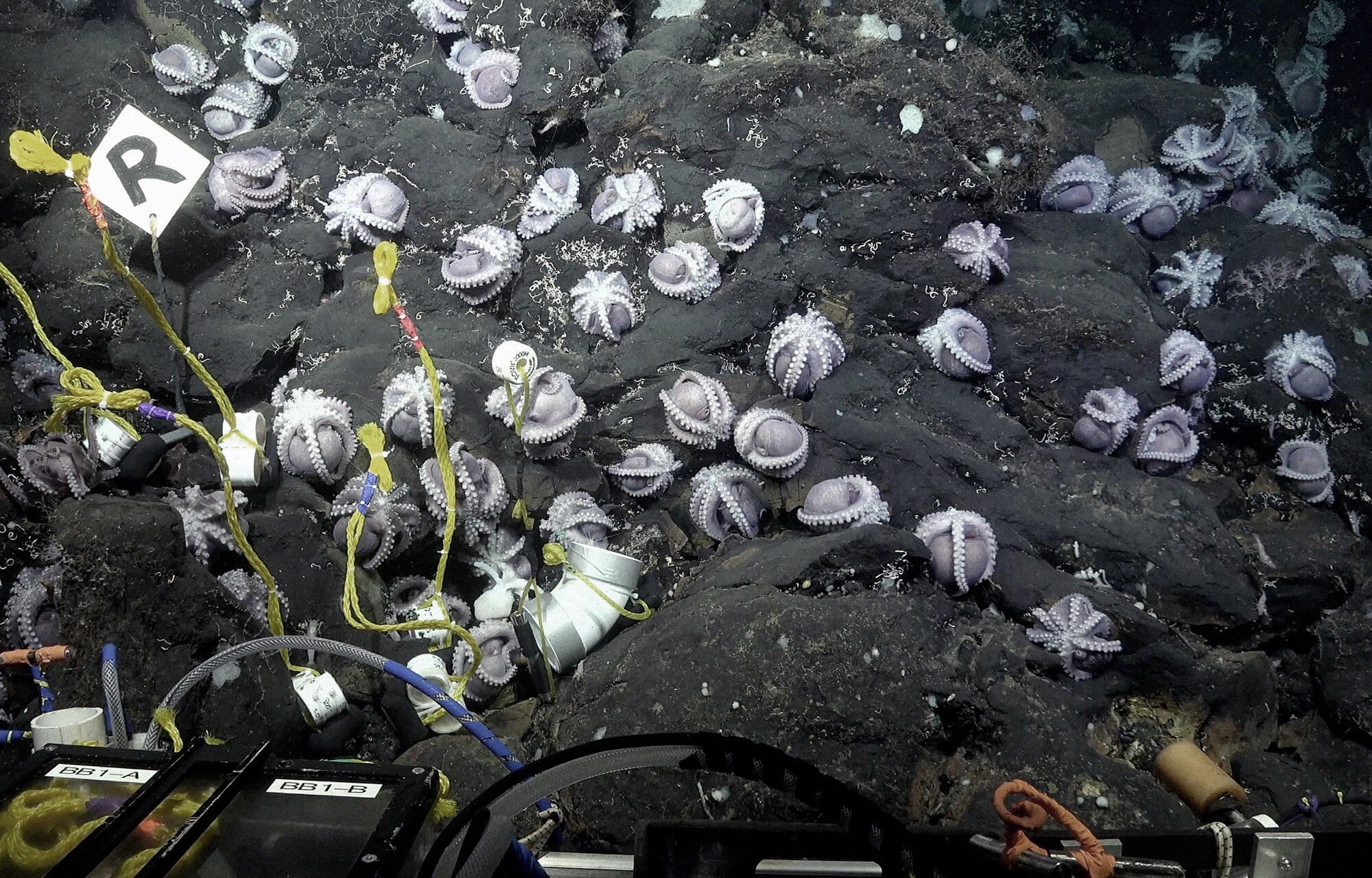

In 2023, away from the chaos taking place on land, scientists aboard the Schmidt Ocean Institute’s R/V Falkor (too) vessel undertook two trips to the depths of the Pacific, in waters off the coast of Costa Rica. During the first expedition in June examining seamounts, the team discovered two octopus nurseries at hydrothermal springs. When they returned months later in December they confirmed that the nurseries were active all-year round.

The expeditions were led by Dr. Beth Orcutt of the Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences and Dr. Jorge Cortés of the University of Costa Rica, whose team discovered four new species of deep-sea octopus, including a new species of Muusoctopus, named the Dorado Octopus after the place it was discovered, a small piece of rock unofficially called El Dorado Hill. Of the new species discovered, only the Dorado Octopus was brooding its eggs at the hydrothermal springs, lending credence to the theory that it has evolved to nurture their eggs in warm water found in the depths.

“Most of what we're finding are probably new species, new records not only for this region, but for the entire Eastern Pacific.”

DR. JORGE CORTÉS — UNIVERSITY OF COSTA RICA

“Through hard work, our team discovered new hydrothermal springs offshore Costa Rica and confirmed that they host nurseries of deep-sea octopus and unique biodiversity,” said Dr. Orcutt. “It was less than a decade ago that low-temperature hydrothermal venting was confirmed on ancient volcanoes away from mid-ocean ridges. These sites are significantly difficult to find since you cannot detect their signatures in the water column.”

The team also discovered a prospering deep-sea skate nursery, appropriately nicknamed Skate Park. Dr. Orcutt and Dr. Cortés took time away on the penultimate day of the December expedition to talk to us – not bad Wi-Fi on the Falkor (too) – about their exciting discoveries and their theories behind the behavior of the octopus breeding in a garden at the bottom of the sea.

Q&A WITH Dr. Beth Orcutt & Dr. Jorge Cortés

On the June expedition you documented and studied nurseries with hundreds of octopus breeding. How has the December expedition been different?

Dr. Orcutt: One of our major goals for the December expedition was to confirm whether the nurseries are active at other times of year, or did we just happen to stumble upon it in June when babies were being born? If you watch some of the footage from this expedition, you'll see that we saw babies being born, as well as eggs all throughout the development cycle – mothers that are young, mothers that are senescent. We didn't have time to explore for other nurseries on this expedition, so we just revisited the two that we knew about from June. In June we deployed several experiments and instruments to try to understand the variability of these vent sites, these hydrothermal springs. A major goal of this cruise was to recover those experiments off of the sea floor and see what the data tells us about the variability of these sites. How is water moving through the seafloor, how warm does it get, how much oxygen does it have? And also to try to study the microbes that live in this system, because we're very curious if the octopus at these hydrothermal springs have unique microbiomes or they're connected to the microbiomes of the environment. Those were some of our major octopus related findings, but we're continuing our journey to understand the biodiversity of the sea mounts in this region, and the abyssal plains.

Dr. Cortés: And the geology.

Dr. Orcutt: And the geology. We found a ton of beaked whale fossils around this region that we'll be sharing with the School of Geology at the University of Costa Rica. There's a lot of research that's going to come out of this, but those are some of our major findings so far. Oh, one more thing – we collected several specimens of octopus between June and now. In addition to the new specimens we collected on this cruise, we're fairly confident that there's at least four species of octopus in this area, maybe more, which is a pretty exceptional diversity of octopus in a relatively small region. That's another exciting finding from our expedition.

And what do you think the reasons for that exceptional diversity are?

Dr. Orcutt: I think it has to do with energy and habitats, if I had to make a guess. We've got these hydrothermal springs, so one species of octopus seems to preferentially brood there. It has an advantage. This is a highly productive oceanographic region, the water column above us has lots of food in it. That supports maybe more octopus than you might find, let's say, offshore the United States or something, where there's less productivity in the water column that rains down and supports the lower ecosystem. So those would be my two working hypotheses of the why.

Dr. Cortés: I agree, and it’s not only the diversity of the octopus but of all the other groups, because apparently there's more food here, which is rare in the deep sea. There's more here because of the Costa Rica Thermal Dome, an oceanography phenomena which results in a very productive area.

You’ve touched on this a little, but what is so fascinating about the El Dorado Hill (previously known as Dorado Outcrop) and what makes it so unique?

Dr. Orcutt: If you were to look at a map of Costa Rica’s offshore waters, you have these underwater ancient volcanoes that dot the sea floor, but the rest of the seafloor is relatively smooth. Whereas if you go further south, off the southern part of Costa Rica and down in Panama, the seafloor is much more rough. Let's focus on the part where Dorado is, El Dorado. What happens all over the world is that water moves through ocean crusts. You see this very spectacularly as hydrothermal vents, but you may not think that the water has to go into the ocean crust somewhere and then come out, but that does happen. The area offshore Costa Rica is one of the best studied in the world for that kind of underground aquifer in the oceans. That's due to the heat that's coming up from the earth, warming the waters in the ocean crust.

You kind of create the siphon effect, where smaller outcrops are places where water comes out, and larger seamounts are places where water goes in. El Dorado is a relatively small feature near a very large sea mount, and we understand that water moves from one seamount out to El Dorado. The waters are warm but they're not super hot, so that means they still have oxygen in them. Organisms like octopus can survive in those places because they can still breathe, but they might get the benefit of the warmth for their eggs to develop faster. That's what makes this a unique place. There's probably other places like this, it's just really hard to find them. It's taken decades, starting from geological surveys, measuring heat flow in the sea floor and going, ‘Why is this place so different?’. Then coming here with remotely operated vehicles ten years ago to find that there's shimmering water here, that there's vents to confirm that. And then this expedition series, ten years later, to actually study the animals.

Dr. Cortés: At this point, only five places around the world have been found with this octopus nursery. Two of them are here in Costa Rica, two in California, and the other one is in Canada.

“We were exploring the seafloor, and being like, ‘Oh, there's all these octopus here, isn't that weird?’”

DR. BETH ORCUTT — BIGELOW LABORATORY FOR OCEANSCIENCES

Were you both on the initial expedition ten years ago?

Dr. Orcutt: I was part of the expeditions in 2013 and 2014. I was a postdoc then, so not the chief scientist. I was part of a team trying to document that there was venting here. We were exploring the seafloor, and being like, "Oh, there's all these octopus here, isn't that weird?" We had no biologists on board. So it wasn't until we zoomed in on them and were like, "Oh, there's shimmering water around them. I guess the octopus are our indicators for where the venting is." At that time that had never been seen before. Some of the scientists on board were also part of expeditions twenty years ago where they did the initial geological studies of heat flow in the system. It’s been a multi-generational team and we've got a lot of young people on board now, so hopefully they'll carry the torch forward.

Dr. Cortés: What's interesting is that ten years ago the eggs didn't look like they had live embryos in them. There's a paper that said they were probably not viable. Then when we came in June, they were there and we saw the babies coming out – that was very exciting.

The octopus are breeding on these low temperature vents and you're trying to figure out the impact that these vents have on the health of the octopus and any eggs that hatch – have you come close to understanding why the octopus are behaving like this? Obviously you theorize that it's good for breeding, but I wondered if there's any more detail about that.

Dr. Orcutt: It's still an active area of investigation, not only here, but at two of the other sites that are offshore California, where they're much closer to land and so they've been a little bit better studied. The research is still ongoing by the experts who are octopus specialists, about the physiology of these organisms, how they actually adapt to live in warmer temperatures. Physiologically, that's hard to do and clearly it's not a widespread behavior because we only observe one species doing that here. It's similar to the species offshore California, although we think it's a different species. So… we don't have a definitive answer of why. Right now the hypothesis is just that the warm water provides an advantage and that these species have come up with both biochemical as well as social changes (most octopus don't want to be around other octopus), to enable them to survive and thrive here.

What other species beyond the octopus are common or thriving here?

Dr. Cortés: We found far more than we expected at this depth. We didn't think there would be so many other organisms but we found a huge diversity of octocorals, black corals, fish, like the tripod fish, lots of sea cucumbers, sea stars, sponges. The list just goes on and on and on. Most of what we're finding are probably new species, and new records for not only for this region but for the entire Eastern Pacific. If you look on a map, it's just a little dot in the middle of the ocean and there's all this impressive diversity. I've been to other seamounts in Costa Rica and they are very different. So each site is different. Even within these small mounts we're looking at, we find different species in each one.

Dr. Orcutt: Some of the really compelling visual footage from our expeditions has been in the water column – amazing jellies and siphonophores. I've done research expeditions all over the world and I've never been to a place that has so much spectacular life as in the water column. That's also something special about this region that connects to that productivity. One of the things that I find really exciting is that we're right on the edge of the Costa Rica Thermal Dome. This is a place that's a little further to the west. So if we see this incredible diversity here but the central dome is even more productive, I just can't wait to see what's in the water column in those places.

How deep are you?

Dr. Orcutt: The average seafloor depth in this region is about three kilometers. The seafloor features that we've been diving on, these underwater hills and knolls and seamounts, range from 150 meters tall to over a kilometer tall. They might be one kilometer long to ten kilometers in diameter. So they really range in this region.

We're talking about positive things, the vibrancy of life that you're seeing on these expeditions, which is amazing. On these expeditions, do you ever see evidence of how climate change or pollution is affecting our oceans?

Dr. Cortés: I don't think we see the direct signals of warming waters or anything, but the warming water is getting deeper and deeper and the waters without oxygen are getting larger, but we're very deep here. Indirectly, climate change will affect all the productivity on the surface, so that would affect how much gets down there. We see evidence of fishing lines, not too much, even though there's a lot of fishing activity here. Also, not much garbage as opposed to other sites I've been to closer to shore, where we see much more garbage than fishing lines.

Dr. Orcutt: What we do see is that you have depth variation in some of the organisms that we find, in addition to kind of the biogeography of whether they're on that sea mount or this seamount. And we know that deep sea species have relatively narrow ranges of temperature that they like to live at. Actually, one of the major technological developments of this expedition is that we've been ingesting all of the video data that we've been creating on these dives into an annotation software platform so that we can identify all the organisms that we see, and then we're going to do that with video from ten years ago, hopefully, to see the changes that have occurred. Those are incredibly valuable baselines for understanding natural variability to see if there are impacts like climate change or ocean acidification, or marine pollution, that are causing issues.

Is one of the octopus nurseries more vibrant than the other? What are the differences between the two?

Dr. Orcutt: El Dorado is much more vigorous. It has a higher temperature. There's water seeping out of a larger area, and so it supports a much larger nursery, with hundreds of octopus. The La Pulperiia site is more contained. The water is not quite as warm, it's only about 7 degrees Celsius compared to background seawater, which is about 2. It has dozens of octopus, not hundreds.

How do you prepare for these trips? Is there anything in particular that you need to do before you go?

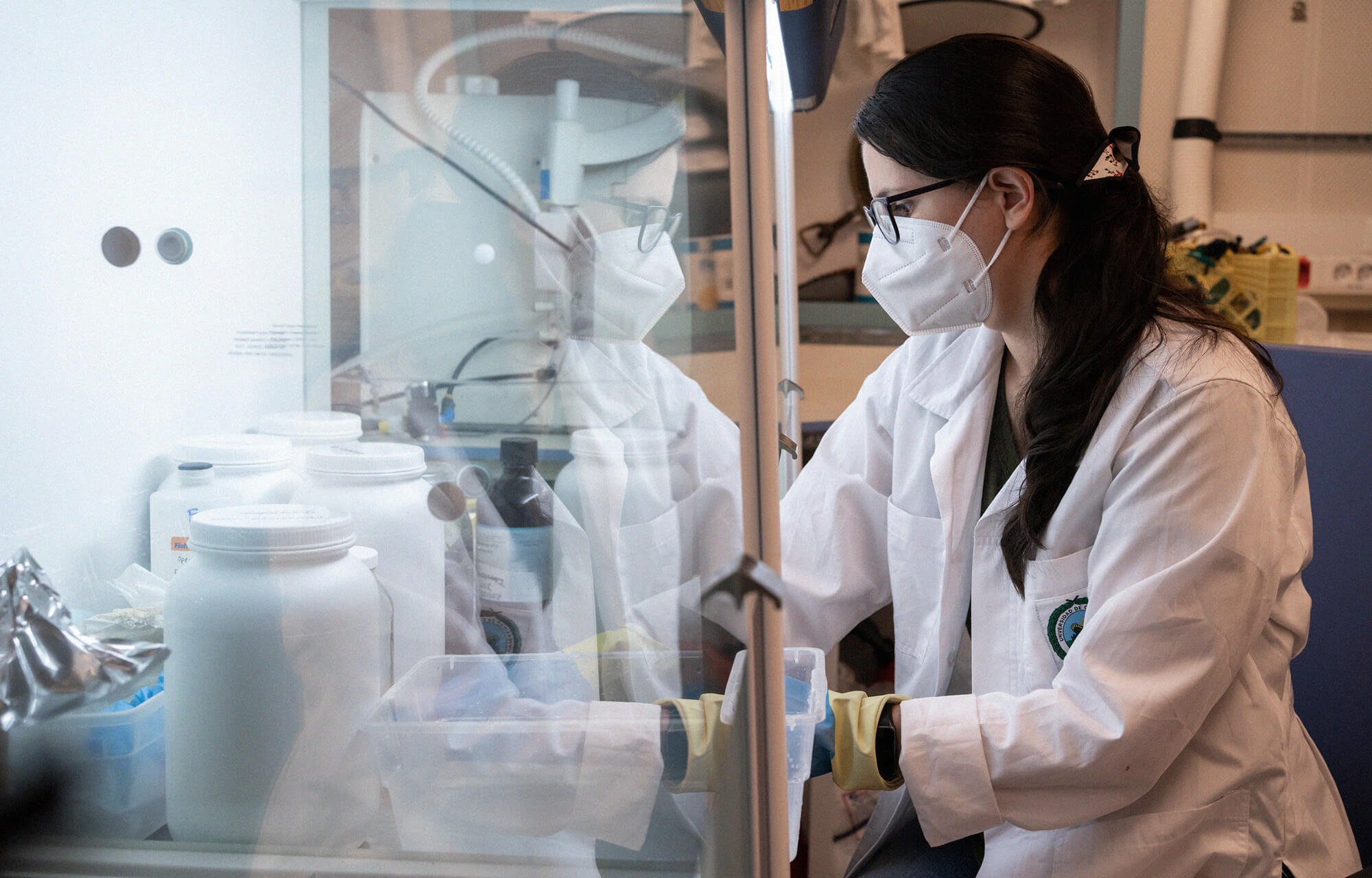

Dr. Orcutt: The planning for an expedition starts years ahead of time. It was 2019 when we proposed this expedition series to Schmidt Ocean Institute, then there was Covid, and they decided to build a new vessel. We made use of that extra time to build up a very collaborative international team. About half of our science party comes from Costa Rica and the other half comes from different parts of the world. So part of the planning is just ’what do we want to do? What are everybody's goals?’ Then what can we fit in the time we have available? We have to request permits from the Costa Rican government to collect samples in their waters, and ensure access and benefit sharing for marine genetic resources. There are lots of planning calls with the Schmidt team, then finally we all get on board and it's 24-hour operations. My job is essentially to be a superintendent, to make sure that we have a schedule and we're constantly adjusting what we're doing, checking our objectives to make sure that things are getting done.

A special part of sailing on the Falkor (too) is that we have this incredible ship-to-shore presence, we are also engaging in outreach at the same time that we're doing all of this science. That takes a different skill set that we have to train each other on – how to talk to audiences about what we do and use this as an opportunity to get people all over the world excited about what we're doing. For instance, yesterday Jorge and other Costa Rican colleagues talked with their National Academy of Sciences about the importance of deep sea research, to try to build awareness for that and support for that in-country. We had a ship-to-shore with the Ministry of Fisheries in Costa Rica, to explain to them. They manage sea fish resources in the ocean, but they don't necessarily think about the deep sea. So we're doing a lot of advocacy at the same time that we're trying to do science. We don't sleep a lot!

Do you have to psychologically prepare for being on a boat for a long time?

Dr. Orcutt: Oh, sure. You have your families at home, you have an actual job at home that you're putting on hold to come out here and do this work full-time, 24 hours a day. Falkor (too) is incredibly connected, so it's not as difficult. But with other expeditions I've been on, it's very hard to call your family, pay your bills, and other things that you need to do. You have to spend a lot of time getting ready. One of the benefits is that it's almost like a science summer camp. You get to go nerd out with a bunch of scientists for a couple of weeks, and that's really nice.

Dr. Cortés: Life continues outside, so you're getting emails all the time like Beth says, paying bills, talking with people, fixing problems. But it's a great experience with this concentration of activities with great scientists and students and this incredible vessel with huge support from the crew. It’s beautiful. As a scientist, it's really nice.

What's the atmosphere on the boat like, particularly when you make a new discovery or you see something unusual? Is there a lot of excitement on board?

Dr. Cortés: Oh yes. All the way from the scientists, who are the first to realize what we're looking at and we start shouting. It's very nice to see the crew run when they hear a scream to see what’s going on, they get really involved with what we're doing. That's great.

Dr. Orcutt: There's a control room, a mission control, where we're on shifts, leading the dive with the pilots, and also narrating the live stream. When cool things happen, it gets very exciting in there. You probably hear it on the live stream. We have a group chat where everybody's like, "Oh, my gosh." Even when it's rocks and sediment, people get excited. You have to make sure to mute your phone when you go to bed because you will get woken up in the middle of the night with some exciting thing.

Aside from the Octopus Garden, what is the most amazing thing you've seen on these two expeditions?

Dr. Orcutt: I mentioned that we saw this incredible biodiversity in the water column. I think another thing that we're very excited about is the discovery of a skate nursery on one of the largest sea mounts in this region, Tengosed. There's a place on that seamount where there's hundreds of skate eggs, and we've sampled some of them and confirmed that they have embryos in them. We also saw what looked like a pregnant skate heading right towards that area. So it’s another deep water species that is choosing this environment to raise their young – another exciting thing for us.

Dr. Cortés: We map everything in great detail. We're going to make a proposal to the Costa Rican government to put official names to these sites and then to the international organization in charge of naming features in the sea. We're putting these spots on the map, so it's not going to be something lost there in the middle of the ocean, but specific sites with names. That's good because then you are creating awareness that these deep water features exist. There's a lot of life down there.