Risky Business: Mining the Deep Sea

"Thousands of meters beneath the azure ocean waters in places like the South Pacific, down through a water column saturated with life and to the ocean floor carpeted in undiscovered ecosystems, machines the size of small buildings are poised to begin a campaign of wholesale destruction. I wish this assessment was hyperbole, but it is the reality we find ourselves in today.”

Dr. Sylvia Earle

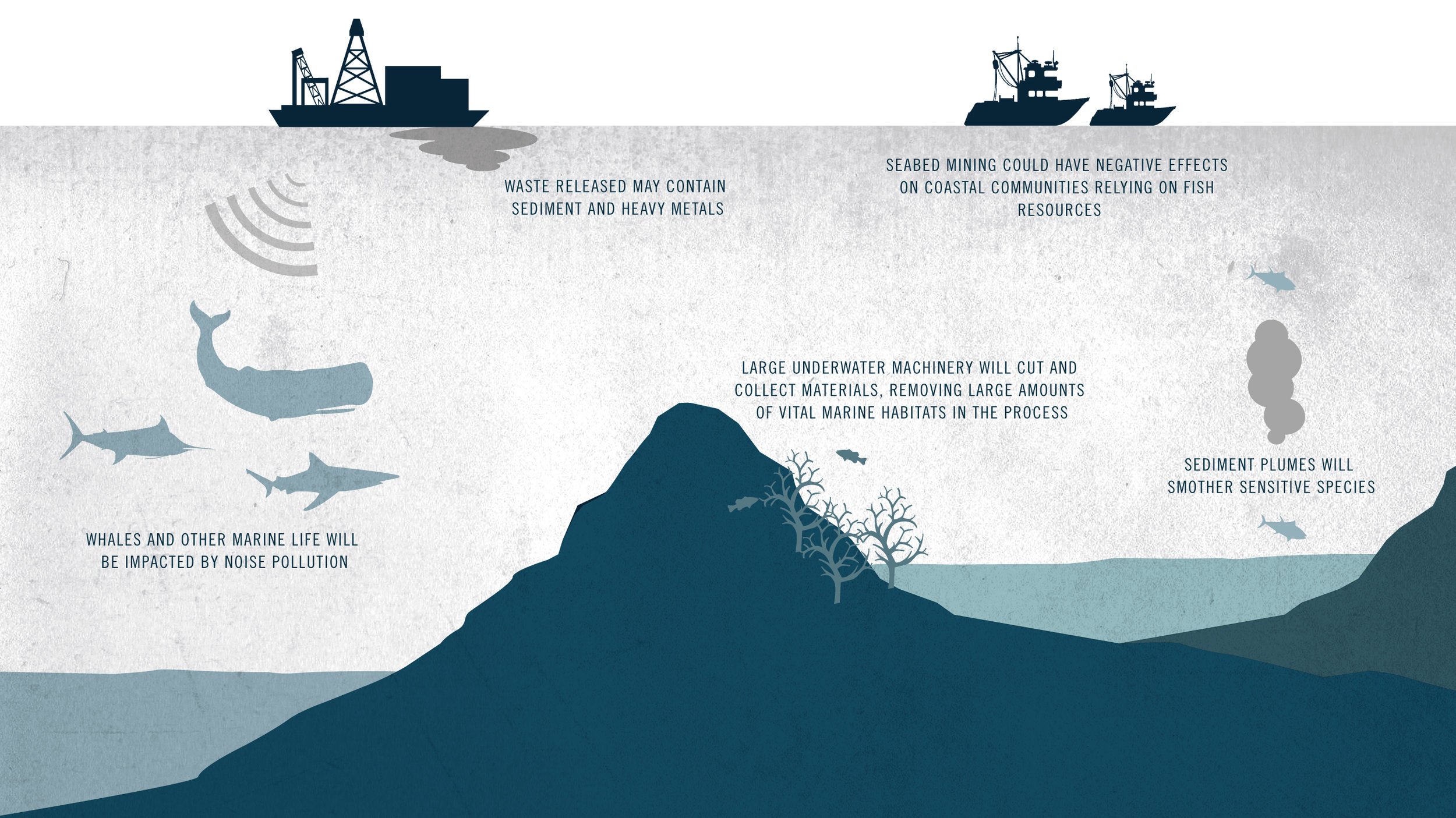

Every year, new images of incredible, never-before-seen species living deep beneath the surface of the ocean circulate online. Images of yeti crabs and alien tubeworms leave people in awe, but even at the ocean’s greatest depths, marine life may be threatened by human activity. Some of the same technological advances that made discovering these creatures possible are now being utilized to prepare for a massive industrial enterprise: deep sea mining.

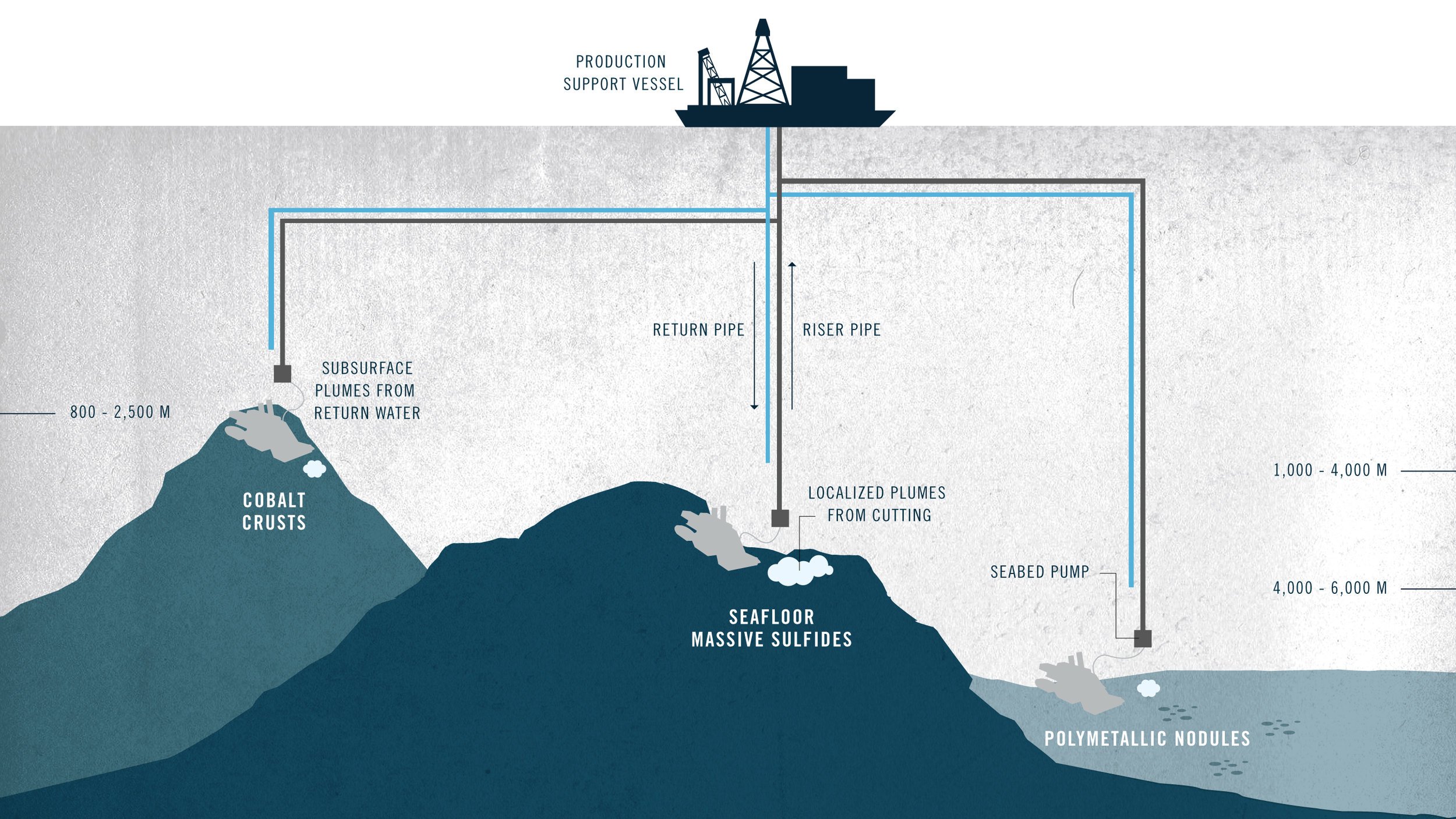

Countries and companies are itching to get access to vast mineral resources located on the seafloor. Three types of mineral deposits exist in the deep ocean. The first, and perhaps most common, can be found in polymetallic nodules, literal nodes of rock built from a million-year process of minerals descending from above and accumulating. Less common, but no less prized by mining interests, are mineral deposits surrounding hydrothermal vents. The vents eject fluids containing traces of various precious metals, again ranging from zinc and iron to copper and gold, that collect around them. The final type of deposit is called a seamount, a seafloor mountain filled with cobalt-rich ferromanganese. Cobalt can be used in pigments, alloys, and, significantly, lithium-ion batteries.

The technology is just now emerging to exploit those resources, and only one organization has the power to regulate mining activity in the vast oceanic expanse: the International Seabed Authority, a UN-chartered organization based in Kingston, Jamaica.

The responsibilities and challenges of the ISA, and its powerful, secretive 30-member Commission, are as complex and important as the area it regulates. Not only are underwater minerals a nonrenewable resource, but the areas of seafloor hosting mineral deposits can also be some of the most biodiverse areas on Earth, previously largely (if not entirely) undisturbed by civilization.

While mining has not yet begun, much of the data that has been collected on the ocean floor has ironically come from mining companies. Over 500,000 square miles of mining contracts have already been given out, an area that collectively is larger than all but 19 countries (it would place just ahead of Peru in the rankings). The contract holders have been busy collecting data on these areas. The data collected by companies in an area near Hawaii, for instance, has been made publicly available and revealed that the seemingly barren seascape under Oceania is actually teeming with diverse life.

Other companies, though, are reticent to release any of their data, making the job of the ISA even more difficult than it needs to be. Yet the ISA itself, whose authority is based on the United Nations’ Law of the Sea treaty, has not been totally transparent. Decisions on biologically sensitive areas can be made with next to no public debate. For instance, a recent approval of almost 4,000 square miles along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge was unanimously approved despite the objections of a World Wildlife Foundation observer. At the time, he Commission gave no indication of whether it had considered the environmental implications of approval at all.

Despite its flaws, this is the deliberative body that is responsible for safeguarding vast swaths of diverse ecosystems, and it has a 2020 deadline for finalizing deep sea mining rules. As the ISA debates, pressure is increasing from countries eager to start mining, and companies are working to improve their technology. Once the ISA concludes deliberations, it is expected that billions of dollars will be invested to push forward into the great abyss, and every investor expects a return.

By Ross Levin

Read more on Oceans Deeply

Seabed Mining: The 30 People Who Could Decide the Fate of the Deep Ocean