SCIENCE VS PLASTIC: STUDYING THE SEYCHELLES

We CATCH UP WITH ALVANIA AND JESSICA LAWEN, THE SEYCHELLOIS SISTERS WHO CO-AUTHORED A SCIENTIFIC PAPER BASED ON FOUR YEARS OF WORK ACROSS THEIR ISLAND NATION

As an organization, we’re often asked why we do cleanups. As an individual, when you’re sweltering under a hot sun, picking out endless plastic fragments from some remote beach, it becomes an almost existential question. With debris continually arriving, is cleaning up even worth the effort? It’s a question we’ve explored before and, since the very beginning, we’ve treated this work as far more than the act of collecting debris. Each event is an opportunity to come together with like-minded, concerned people who want to make a difference. Every cleanup offers new opportunities to learn, share, explore and educate in different environments – ranging from isolated beaches to muddy mangroves. Finally, every cleanup generates vital data through our long-running protocol for measuring the amount, type and location of waste collected – work that has now led to a scientific paper by two of our youngest country coordinators.

Alvania Lawen founded Parley Seychelles when she was just 18, building on nine years (!) of prior activism in her home country. Since then, she’s gone on to win a scholarship to study Environmental Management and Sustainability at the University of Plymouth in the UK. With her sister Jessica now heading things up in Seychelles, the stage was set for a deeper dive on what they were finding and what lessons could be drawn. Based on four years of hard work across the Seychelles, spanning 53 cleanups on 10 islands, the Lawen sisters co-authored a scientific paper published in the prestigious Marine Pollution Bulletin entitled Beached plastic and other anthropogenic debris in the inner Seychelles islands: Results of a citizen science approach. We caught up with Alvania and Jessica to find out more.

Q & A

How did the whole study get started – when did you first think about writing a scientific paper?

Alvania: I think it dates back to working with Parley in 2019, when we did the World Cleanup Day cleanups and HQ had sent us a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) developed by Dr. Sarah-Jeanne Royer about how to measure microplastics. We’ve been recording data since then, and logged over 50 cleanups around Seychelles, but I didn't really know the process of turning that into a paper. I met our co-author, Andrew Turner, at university in Plymouth, and we started discussing all the data we had, and how with some statistical analysis it could become something more.

Was there much to build on, or were you starting from nothing?

Alvania: Well that was one of the things – there's never been a paper about plastics in the inner islands of Seychelles. There's been one paper written about pollution on the island of Cousine, which is close to one of our Clean Waves islands actually, and a few studies on the outer islands, but in general Seychelles is understudied. So making our data into graphs, I nearly cried when I saw it because it was four years of work. I started Parley Seychelles when I was just 18 and now I'm 23. It was just crazy that I saw all of it on a graph and that made me cry because I was, “My gosh, this is incredible.” Four years being out in the field and all the challenges and also all the good things and then all now in a graph. It was crazy for us. It got me excited because although we had said we're going to write the paper I didn't actually see it in my head until then.

What was the process like?

Alvania: After Andrew had crunched all the data, the three of us got started on the draft, making it what it is now and also finding peer reviewers. One of the appeals for journals, I think, was that Seychelles is an understudied area. But when Andrew told us it had been accepted for Marine Pollution Bulletin we were blown away – that's the highest level of journal for marine pollution. There's so many other journals and there are people who have a PhD and haven't published that high up or haven't published in something like that – so it was very daunting. The review process was very, very difficult but we worked through it together. The reviews gave us the opportunity to include Parley’s protocol when it comes to separating plastics, because we separate different plastics, and we also differentiate between locally washed-up trash and fisheries-related debris.

What would you say are the key findings? What jumped out for you?

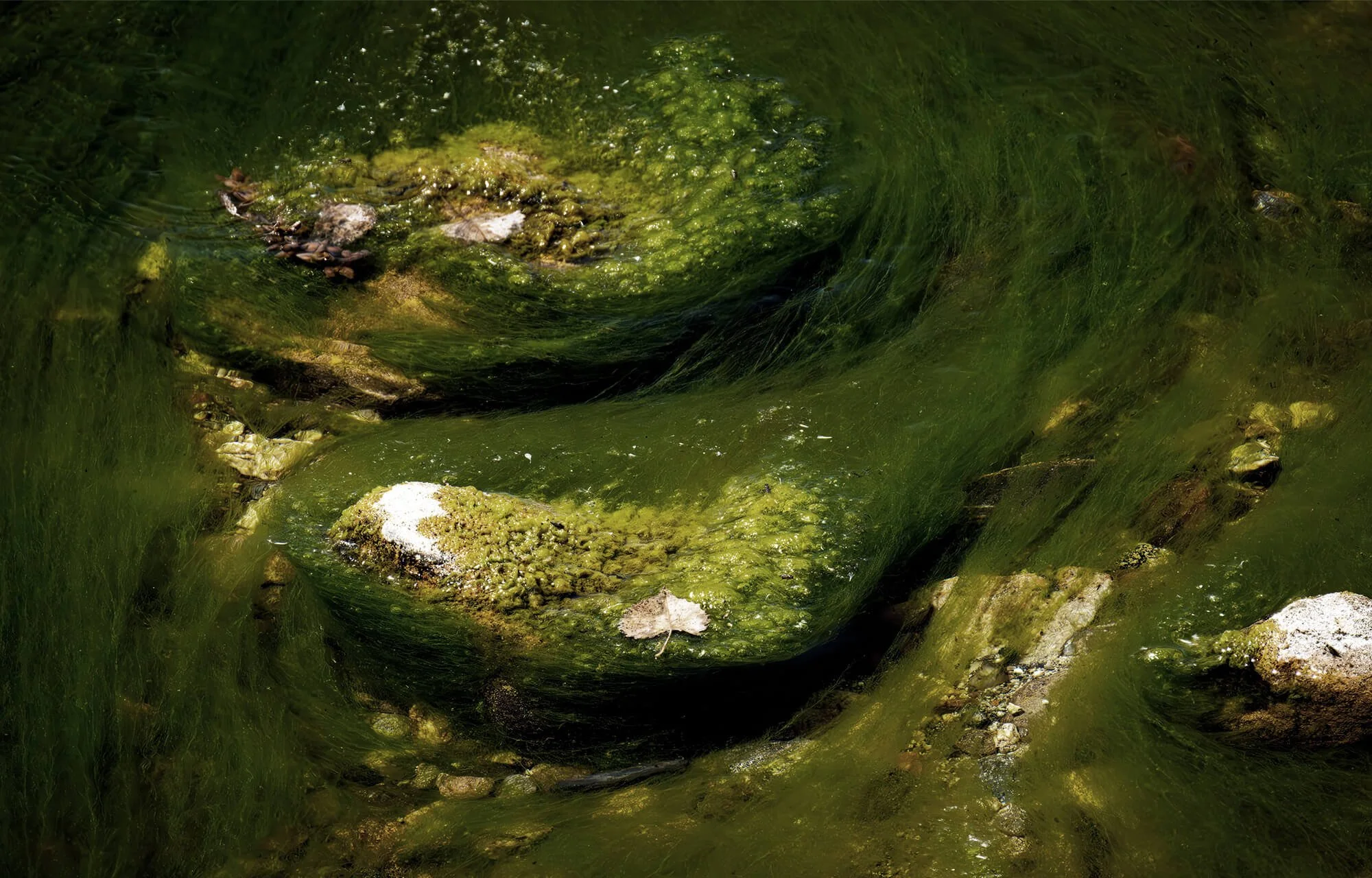

Jessica: I think probably the role of vegetation in trapping plastic – and learning where it comes from. We saw a lot of local trash, but also items like capped PET bottles which had drifted in from ships or from other countries via ocean currents. The majority of the plastic over 53 cleanups was collected from the back beach, and was often captured by or entangled within beach vegetation and rock formations. Local, land-based plastic pollution was mainly food packaging from locals, visitors, tourists and hotels, with PET bottles exceeding 100 on several beaches on Mahé but totally absent from more remote island beaches like Félicité.

Alvania: I think this highlights the importance of having vegetation, coastal vegetation. For a long time, the most commonly known benefit of having coastal vegetation was erosion prevention. It's an ecosystem-based adaptation technique, because these plants have lots of roots and they hold the sand back – but we now know they also trap pollution. That will be helpful for us small island states, especially with sea levels rising. We've known that about mangroves for a long time, but then actually seeing it with just any other coastal vegetation is amazing.

In preparing the paper, did you learn anything new about either globally or specifically for the Seychelles, what we should be focusing on for reducing plastic pollution?

Jessica: Just in general, first of all, stop littering. That has been said so many times. We have so many adverts in Seychelles on top of this and massive public awareness, but that's still the primary focus for me as a Seychellois, because the plastic problem is such a huge problem. At least limit it, at least make it a bit easier, just stop littering to begin with. But then the ultimate solution is just to stop plastics…

Alvania: …and find plastic alternatives. That's what's needed because it is just such a huge problem. As our founder Cyrill puts it, plastic is a design failure, it's a victim of its own success. It is just terrible because for instance, small island states like us or low income countries or developing countries, we obviously have a less stronger economy. So the options of the things that we import will most likely be cheaper options – there's less alternatives for us.

You're still both young, you've now published a science paper, so for other young folks – especially from the global south – what advice would you give?

Alvania: I'd say first of all, I'm not special. I'm only here because I had access to this because I worked for Parley and I came to university here in the UK on a scholarship from our government. So then I get an institution that I can tap into the procedure, the process and be able to publish a paper. I'm pretty sure there are millions of people in the global south countries that would be able to do the same, who are as intelligent, but there are so many barriers. First of all, the language of science is English and there's a lot of published papers in the world that are amazing but are not in English. So just first of all, go and make it more accessible. There's a push now for that. There's more opportunities, more scholarships being advertised to global south countries and some changes in the system in certain countries, not all unfortunately, to make it more accessible for people to come to university.

You're graduating in August – do you plan to return to Seychelles or what's the next step for you, Alvania?

Alvania: Yes, most definitely, I can't wait to go back home. I miss it so much – and I can't wait to join the activism again. I would also love to continue in research. I’ve found a love now for it. Coming into the world of academia at university and loving my country so much, I just want to write about Seychelles for every assignment and I can make any assignment relevant to Seychelles. There’s very little specifically about our country, but also small island states in general. It's very, very hard because it's very limited and there's so many amazing things happening in small island states when it comes to climate change mitigation, when it comes to solutions. We talk a lot about problems when it comes to the environment. Small island states are amazing because we have limited resources, but we are passionate. We have this fire inside of us, and that translates into our environmental activism as well. We'll make anything with the little amount of resources we have. I don't know what's in your fridge right now, but I could cook a dinner with what you have – and that's every islander. Meeting islanders here at the university, I realize that it's crazy: we have the same culture spread out across the world, even though we're so far from each other.

Jessica, what's next for Parley Seychelles?

Jessica: I'm patiently waiting for Alvania to be back so we can make our work even more impactful in Seychelles. I've been basically alone for the past few years and I really miss my sister! The paper, well, I keep telling everybody, it is Alvania's hard work. I'm basically just a data collector. I reviewed the paper of course, but then it's all Alvania's hard work. She was so stressed doing this and she's called me a few times saying "Oh, I don't know if this is going to go through. I don't know how... I'm not motivated to go on." Even for me, sometimes you just feel uninspired and then something happens. Doing this work, you just meet so many people, and especially young people, and then it's just, your inspiration's renewed.

"there's so many amazing things happening in small island states when it comes to climate change mitigation, when it comes to solutions."

Alvania Lawen